Audio Player

From Nigeria through Niger and Burkina Faso, the ambitious Great Green Wall (GGW) project faces a daunting obstacle: persistent conflict and insurgency that threaten to derail decades of environmental restoration in one of Africa’s most fragile regions.

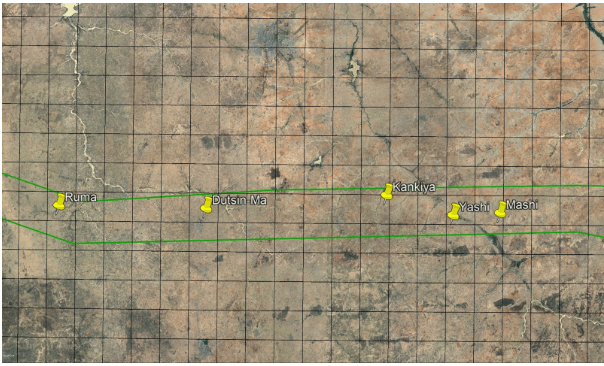

Recent geographic information systems (GIS) analyses track tree populations using an 18 by 18 km grid through the GGW corridor across multiple communities in Nigeria, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Comparing data from 2007 to 2025, the findings suggest that out of 30 locations surveyed, insurgents have a presence in at least 24, and three more show signals indicating their possible activities. This persistent insecurity is reversing tree gains and undermining restoration efforts.

Niger’s central role in the GGW is pivotal, given its location in the Sahel—and the enormous environmental challenges it faces. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, Niger is among the world’s poorest countries, with up to 80% of its population relying on rain-fed agriculture. Sadly, close to 75% of Niger’s land is classified as desert, and an estimated 100,000 hectares of arable land are lost to desertification every year.

The World Bank estimates that the Great Green Wall project could “restore 3.2 million hectares of degraded land” in Niger and “ensure food security” for rural communities. Nevertheless, environmental groups warn that insecurity is making such goals increasingly difficult to reach.

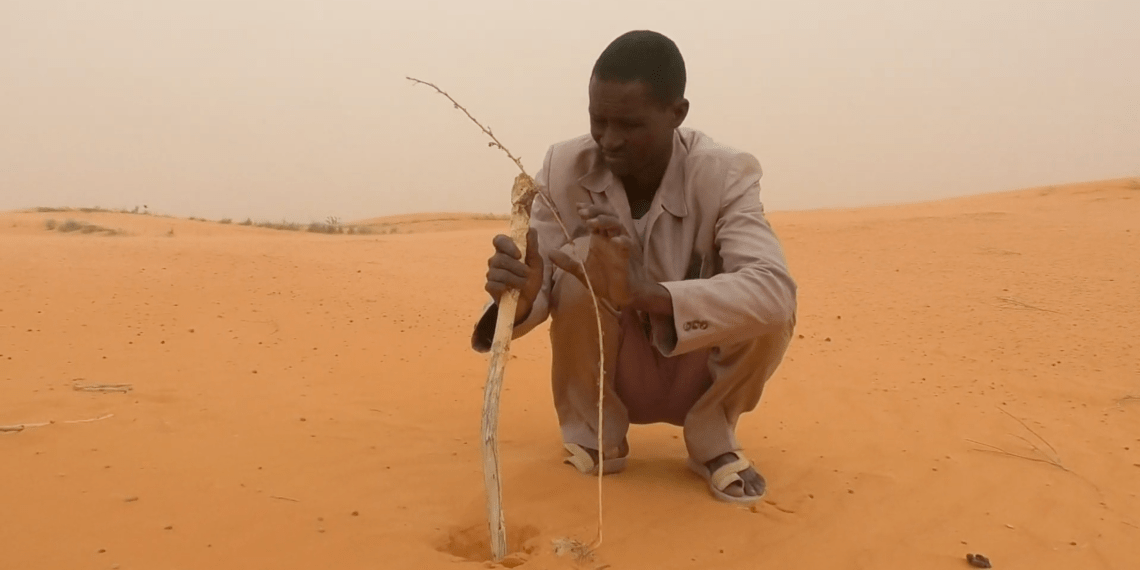

In Banizoumbou in the Niamey region, not far from the Malian border, the Niamey Tree Initiative once launched a 10-hectare volunteer programme to teach women and youth how to restore degraded land using Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR). But Mr. Moumouni, director of L’Initiative pour l’Arbre, an environmental non-profit, told us: “Everything was ready. But by April, armed groups had moved in, forcing villagers to flee. We couldn’t deploy a single team.”

The consequences of violence and displacement are tangible. According to the UN Refugee Agency, at least 240,000 people were displaced by armed violence in Niger’s Diffa region as far back as 2017, a number that has reportedly risen. Many of these displaced were farmers or herders who would otherwise have supported the long-term care of reforested areas.

In places like Chetemari and N’Gagam in Diffa, insecurity has forced even the most dedicated environmental groups to abandon their work. Abdoul Aziz Mohamed, president of the Youth Association for the Protection of the Environment (AJUPE), explained: “We can’t go back. Even if we try, we’d need a military escort, and the cost of just one is more than our whole seedling budget.”

Ideally, NGOs and agencies would revisit sites to assess growth, replace any lost seedlings, and train locals on sustainable land management. But in insecure zones, planted trees are withering, sand dunes are advancing over reclaimed land, and communities are left without support.

The result is that projects once designed to restore ecosystems and ensure food gardens have been abandoned or forgotten, according to Mr. Mohamed. In many places in Diffa and Tillaberi, the harsh reality is that the desert is taking back land once nursed back to health.

Environmental Decline and Some Pockets of Progress

According to detailed satellite imagery, large swathes of Niger’s agricultural zones—especially the southern fringes of Tahoua, central Tillabéri, and western Maradi—are sliding deeper into ecological decline. Over 2.5 million hectares have gradually succumbed to sand, driven by climate change, overgrazing, and deforestation.

Yet not all is bleak. Despite rising insecurity, certain regions—like parts of Dosso and Zinder—show impressive results thanks to time-honoured agroforestry methods such as Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR). According to recent GIS data, these practices have rejuvenated over five million hectares of degraded land, facilitating the growth of around 15 million trees—a significant achievement in reversing land degradation.

Nevertheless, the strides made are at risk. Armed conflict in parts of northern Tahoua and western Tillabéri has erased years of progress, GIS investigations confirm. Satellite data through 2020 indicates that some 1.8 million hectares of restored land in these conflict-affected areas now show sparse or no vegetation cover.

Analysis of GIS data tells a stark story: From 2010-2015, Niger consistently expanded rehabilitated land by nearly 400,000 hectares annually. But since 2016, coinciding with a surge in jihadist activity around the tri-border region, this progress stalled and many formerly “green” patches are now void of plant life. This direct link between insecurity and environmental backsliding highlights a worrying trend for the entire Sahel.

But it is not only violence that is harming the land. In places such as Filingué in Tillabéri, forest loss is driven by persistent human activity. Local officials explain that, amid waning security presence, loggers often work at night, stripping landscapes once dominated by hardy acacias and resilient baobabs. In Filingué, the local environmental office notes over 3,000 trees felled annually, leaving the roots bare and the once-green townscape stripped.

National data mirror these local trends. In 2020, Tillabéri maintained about 12,600 hectares of natural forest—just 0.14% of its area. But by 2024, four hectares had also vanished, adding almost 800 tonnes of CO₂ emissions in that period.

In the east, Diffa faces a different challenge. As refugees fleeing Boko Haram in northeastern Nigeria flood into the region, limited options for fuel and shelter force many to rely on trees for warmth, food, and income. As a result, areas that were once leafy are now barren—sometimes you could walk a kilometre without seeing an upright tree.

Moussa Bagana, a University of Diffa researcher, said, “It’s hard to even count how many trees have been cut. You see the entire bush stripped to the stumps—whole woodlands erased.” He warns that when slow-growing desert trees are removed, the ecological effects in arid regions are especially severe.

This loss of tree cover is not new but represents a decline spanning more than two decades. According to Global Forest Watch, from 2000 to 2020, Diffa lost about 578 hectares of tree cover—a staggering 52% reduction. Satellite imagery between 2016 and 2020 further reveals that over 50,000 hectares in Filingué experienced notable canopy shrinkage, while Diffa’s forest cover dropped by nearly 20%. Forests once shown on regeneration maps as thriving now appear as stretches of sand and scrub.

In total, between 2001 and 2024, Niger reportedly lost one hectare of detectable tree cover—a 55% dip from its 2000 baseline—resulting in approximately 1.04 tonnes of carbon released into the atmosphere. Regions like Tillabéry, Dosso, and Diffa alone account for about 60% of national tree cover loss.

Although the African Union’s GGW initiative offers hope, environmental experts in Niger point to a dysfunctional institutional structure—along with insecurity—as the biggest barriers to real progress.

Beyond security challenges, insiders claim that ineffective budgeting and misplaced priorities have dogged the very agencies tasked with fighting desertification. This organizational inertia not only stifles restoration efforts but breeds mistrust among local communities and international partners.

Oversight, Funding, and the Reality on Ground

An examination of Nigerian government budget documents shows the National Agency for the Great Green Wall (NAGGW) received nearly ₦5 billion recently. Of that, less than 10%—about ₦372 million—supported actual tree planting. The rest was allocated to unrelated items, like solar street lights, school buildings, and road projects. Interestingly, many of those projects went to Yobe State, from where the current and previous agency heads hailed. Notably, ₦25 million was budgeted for streetlights in Kubwa, Abuja—a location far removed from GGW operational zones.

In 2024, the agency’s budget soared to ₦21.9 billion. Though spending on afforestation rose slightly, problematic allocations persisted, with over ₦4 billion set aside for roads, solar infrastructure, and youth initiatives that were only loosely connected to environmental priorities. According to a June 2025 Freedom of Information request by PREMIUM TIMES, officials have yet to respond to inquiries about these budget discrepancies, even after acknowledging receipt of the request.

Environmental justice advocates fear that this disconnect between mission and spending erodes the credibility of the Great Green Wall. “When funds meant for tree planting are diverted to other projects, it damages trust and slows down our collective progress,” said a local activist who works with affected farmers.

This trust deficit surfaces in Gidan Gabas, Kano State. Authorities launched a five-hectare woodlot there with much fanfare, but failed to provide water. The seedlings perished. In other locations like Yobe and Adamawa, farmers have overtaken abandoned planting sites for crops, despite initial GGW intentions. As a result, the “forest” never materialized, and locals now question the commitment of project leaders.

These challenges mirror broader struggles in West Africa. Government agencies often face limited capacity, fragmented leadership, and competing interests—problems that have a direct impact on Nigeria’s environment and economy. Since its start in 2015, Niger’s national GGW agency has worked with limited reach. It lacks a robust presence across Niger’s eight regions and does not possess the resources or technology to adequately monitor or unify projects run by NGOs, donors, or community organizations.

Most of the success stories since 2015 are due to external partners. Between 2015 and 2019, Niger’s direct budget allocations led to just 1,780 hectares restored. In contrast, NGO ID-VERT—with international backing—successfully rehabilitated almost 300 hectares and planted more than 120,000 seedlings in Diffa during the 2024–2025 campaign. Similarly, ProDAF, another donor program, developed 150 hectares by planting 1.5 million seedlings from 2018 to 2021.

Earlier data by the national agency suggests that, from 2011 to 2015, about 359,530 hectares were restored. But the majority of this progress came from decentralised, donor-driven interventions—not unified national planning.

Ironically, even with institutional weaknesses, Niger remains a leader among the GGW’s 11 participating countries, showing the complexity and ambition of landscape restoration across national borders.

The Road to 2030: Can the Great Green Wall Succeed?

Less than half of the GGW’s original targets have been met, just five years from the 2030 deadline. According to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the project needs an extra $33 billion to meet its full goals.

At a 2021 summit, donors collectively pledged $19 billion, but by March 2023, less than $2.5 billion had actually been delivered, with the bulk of funds allegedly due by the end of 2025. Last year, United Nations Summit on Desertification president Alain Donwahi acknowledged the project had fallen behind schedule, citing delays in financing and implementation. “It is an understatement to stress that we are not in line with our common objective to complete by 2030,” Mr. Donwahi said.

These financial and security hurdles threaten to undermine one of Africa’s most critical climate and development initiatives. The consequences of failure are not just local: they risk deepening poverty, hunger, and instability across the Sahel—a zone already stretched to its limits by rapid population growth and changing weather patterns.

For Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, and the broader West African region, the fate of the Great Green Wall carries urgent environmental, economic, and social implications. Addressing insecurity, improving transparency, and recalibrating priorities are essential steps if this ambitious dream is to survive and thrive.

How do you think Nigeria and its neighbours can overcome the current challenges facing the Great Green Wall? What creative solutions or local actions have inspired you in your own community? Share your perspective below—and join the ongoing conversation about restoring our continent’s green future.

Have a story or inside information about community reforestation or climate initiatives? We want to hear from you! Email us at story@nowahalazone.com if you’d like your story featured or are interested in selling your exclusive story.

For general questions or support, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com. Got tips about environment, government accountability, or rural development? Drop your thoughts or stories—we’re always ready to amplify local voices.

Follow us for the latest updates, analysis, and public discussions on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

Join the conversation—your views matter!