As my plane approached Kinshasa, my eyes were instantly drawn to the mighty River Congo snaking its way across the landscape—a striking first impression for any visitor to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Flying in on African World Airline (AWA) Flight 342 from Accra, I watched as the aircraft circled, awaiting landing clearance due to a ‘VIP Movement’. The sweeping view of the river’s silvery ribbon temporarily soothed the tension of the wait.

Once the clearance came, our descent began through thick clouds before bursting into Kinshasa’s radiant sunlight. As we dropped lower, the true scale of the Congo River revealed itself: wide, winding, and fanning out into a network of tributaries stretching towards the Atlantic. For many Africans, the River Congo holds nearly mythical status. According to the World Atlas, it is Africa’s second-longest river after the Nile and second only to the Amazon in global discharge volume. It also claims the title of the world’s deepest river, plunging more than 220 metres (720 feet) below the surface in parts. This vast waterway forms the largest network of navigable rivers in Africa, linking remote towns and cities deep into the continent’s interior.

My fascination with the river led me to its banks within my first day in Kinshasa. That evening, I joined crowds at the riverside in the Gombe district—joggers, families, couples, and solitary wanderers all drawn to the shores. The air was cool and breezy. There was a hum of lively conversation and laughter, all set to the background music of the flowing river.

For the youth, this river is a source of excitement and escape. For writers and dreamers, it inspires stories and reflection. Even with its association with Congo’s turbulent history, the river remains a source of unity and hope for locals, serving as a lifeline and a border between Kinshasa and its sister city, Brazzaville—the capital of the Republic of Congo. These two cities, separated only by the wide expanse of water (and a distant bridge), are among the only national capitals that sit directly opposite each other across a major river.

Despite their proximity, the differences between these “twin” capitals are striking. The DRC, with a population nearing 100 million and an area of over 2.34 million square kilometres, dwarfs its neighbour. Kinshasa alone is home to around 17 million people. The Republic of Congo, meanwhile, has a population of roughly 5.3 million, with about 2.3 million residing in Brazzaville. Interestingly, while international visas separate most travellers, citizens of both Congos reportedly cross without visas—a rare exception in modern Africa.

The Congo River is more than a boundary or practical waterway. It fuels Africa’s greatest hydroelectric potential. According to reports from the African Union, should the river’s capacity be harnessed fully, it could power half the continent. The river also has a literary legacy, immortalized in Joseph Conrad’s 1902 novella “Heart of Darkness”, a text that sparked global conversation on colonialism and exploitation. While Conrad’s perspective has often drawn criticism from African writers and historians for its Eurocentric gaze, the river’s real legacy is one of resilience and possibility in the heart of Africa.

Keen to connect with this powerful symbol, I took off my shoes and dipped my feet in its warm waters—a symbolic tradition whenever I visit a legendary body of water. My interaction, however, was quickly interrupted by a warning from a French-speaking local: “Attention monsieur, il y a des crocodiles dans la riviere!” (Be careful, sir—there are crocodiles in the river!) Such moments underscore the living wildness of the Congo.

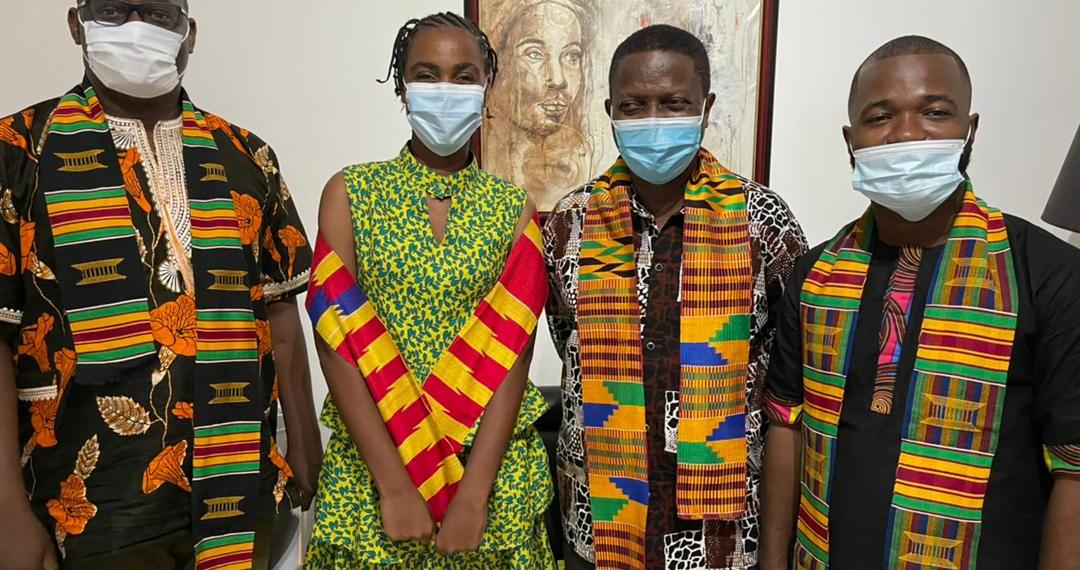

My trip to Kinshasa was at the invitation of the Congolese Writers Association to celebrate the inauguration of the Pan African Literature Prize, endowed by President Felix Tshisekedi, current Chair of the African Union. The schedule included meetings with government officials and literary figures— and a chance to experience the city’s vibrant culture firsthand.

Kinshasa, formerly Leopoldville, became a Belgian colony in 1908 and later transformed into the DRC, the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa and second only to Algeria in total area. With about 100 million inhabitants, it is the world’s largest French-speaking country and the fourth most populous in Africa, after Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Egypt.

Signs of the city’s lively chaos greeted me from the airport. Heavy rainfall had left roads waterlogged, echoing experiences familiar to anyone who’s navigated the potholes and traffic jams of Lagos. Vehicles crept along, and commuters jostled for buses and taxis—a reminder of big city life in West Africa. Eventually, my hosts and I reached my hotel, the Hacienda, set in the upscale Gombe district.

The next day opened with a meeting with the President of the Congo Writers Association, Bia Bietusiwa, and his team. From there, we visited Kasa-vubu—a district named after Congo’s first President. Key city arteries like the Boulevard du 30 Juin, commemorating Congo’s 1960 independence, revealed Kinshasa’s proud (and still evolving) identity.

I also paid a courtesy visit to Madam Yvette Tabu Minangoy, the city’s Hon Commissioner of Arts and Culture. The tour passed key landmarks: the Cathedral Notre Dame, the Boulevard Triumph, and the iconic People’s Palace—reportedly built with Chinese support during Mobutu Sese Seko’s era. We also viewed the vast Stade des Martyrs, boasting a capacity of 125,000 and serving as a home for DRC’s top football clubs.

Throughout the journey, it was evident that COVID-19 protocols were lax. According to local residents, skepticism about the pandemic meant masks and distancing were rare sights. Public health officials in Kinshasa have reportedly continued sensitization efforts, but uptake remains low—a trend seen in several parts of West and Central Africa, though attitudes vary widely by city and community.

That evening, I attended an open-air reception for the Pan African Literature Prize delegates at the colonial-style residence of Madam Kathryn Brahy, General Delegate of Wallonie Bruxelles International. Diplomats, writers, and culture advocates mingled to the sound of classic Congolese music. Even a sudden drizzle couldn’t dampen spirits as we retreated indoors, continuing the celebration of art, music, and literature.

Kinshasa’s energy is palpable. With a population rivaling Lagos and Cairo, it is the world’s largest Francophone city; French dominates in official settings, while Lingala pulses through its streets. The city has been the backdrop for DRC’s dramatic history, including colonial occupation, liberation struggles, military rule, civil war, and ongoing challenges with militias in the east. But for all its past and present troubles, Kinshasa remains a place of festivity and colour. Local music—especially the irresistible rhythms of Rumba Lingala—permeates daily life, much like Afrobeats does in Nigeria. Icons like Franco Luambo, Tabu Ley, Papa Wemba, and Koffi Olomide have given Congo music global reach, playing a role in shaping Africa’s musical landscape. My hosts, eager to share their culture, loaded my phone with playlists of these legendary artists—providing the nightly soundtrack to my stay.

The major event of my visit—the Pan African Prize inauguration—took place at the National Museum, an institution built through international collaborations and a symbol of cultural revival. Traffic jams, another Kinshasa staple, meant my interpreter and I had to abandon our cab and catch a “moto”—Kinshasa’s version of okada—to make it through. Maneuvering through gridlocked vehicles was an adrenaline-packed experience reminiscent of chaotic Nigerian city commutes, and proved that sometimes, a motorcycle is the only way to beat African urban traffic.

The following day included an official tour of the riverside Presidential Palace (Palais de la Nation), a site heavy with the symbolism of Congo’s leaders and history. At the entrance stands the massive tomb of former President Laurent Kabila, marked by a tent-like structure supported by four giant fists and crowned with a golden star. Though I could not enter due to the hour, I was told the former leader’s remains rest there, alongside an eight-meter-tall statue in his honour. The forecourt of the palace felt thick with the memory of the country’s storied political figures—from Patrice Lumumba to Mobutu Sese Seko and beyond.

My last official engagement took me to the National Institute of Arts (INA) in Flambeau Gombe, where a lecture on the role of French in African literature was delivered by Prof. Andre Yoka Lye Mudaba. The session was attended by writers, musicians, and actors. Performances of poetry and music, including a fast-paced national anthem, brought to life the city’s blend of tradition and creativity. The professor’s lecture stressed the importance of linguistic versatility, arguing that opening up French-speaking nations to English would foster broader literary exchange across Africa—a perspective gaining ground across many African cultural institutions.

Afterward, as dusk fell, my local hosts introduced me to the nightlife in Barndal and Matonge—districts known for open bars, lively music, and street food. Revelers unwound with drinks and laughter, and I discovered that grilled turkey bottoms are a culinary favourite in Kinshasa, sparking laughter and camaraderie. The evening ended with a farewell celebration at the Writers’ Secretariat—an occasion marked by generous food, drinks, and, of course, Congo music performed with joy. The more the refreshments flowed, the higher the energy and volume of the songs—a fitting finale to a week in a city where creativity, resilience, and a zest for life persist, even in challenging times.

Kinshasa’s story, in many ways, mirrors Nigeria’s: a tale of a city that never sleeps, of hopeful people confronting political and social upheaval with undiminished spirit. With its cultural depth, festive rhythms, and enduring optimism, Kinshasa stands as a testament to the dynamism found across Africa’s great cities.

Have you experienced the energy, music, or culture of Kinshasa, or another African megacity? How do you think Nigerian and Congolese cultures compare? Share your experiences and join the conversation in the comments. Don’t forget to follow us for more stories on Africa’s diverse cities and people!

For general support or inquiries, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Want to join our growing community? Follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram for the latest on African news, lifestyle, business, and entertainment!