With more than 40 million Nigerians living with mental health disorders but just about 200 psychiatrists available nationwide, the vast majority—over 85 percent—find themselves without dependable, accessible mental healthcare. Under tough economic conditions and in a country where basic services often falter, mental health experts repeatedly stress the urgent need to bring quality mental health services into primary healthcare, especially for those in underserved rural areas. As recent revisions finally revisit Nigeria’s long-unimplemented Mental Health Policy (inactive for 36 years until its 2023 update), the nation continues to struggle under an economic burden estimated to exceed N21 billion each year.

Obanor E.O., once a line supervisor earning N220,000 monthly at a well-known Lagos bakery, lost his job in late 2020. Despite his qualifications as a sociology graduate and additional certification in catering, he spent most of 2021 applying in vain for over 30 new roles. Discouraged but resilient, Obanor started his own pastry business—only to have rising costs for flour, oil, and other materials, sparked by the fuel subsidy removal, eat away his capital just as he welcomed a second child.

The growing cost of living quickly overtook his resources, pushing him to the brink mentally. Suicidal thoughts became a daily battle until opportunity knocked: one employer finally responded to his months-old application, offering him a much-needed reprieve.

Chukwuma Ibezim, a hardware dealer in Ikeja’s Computer Village, shared another story. His neighbour, Kunle “K,” a much-liked, well-mannered young man, began showing signs of distress after being defrauded at work. Neighbours noticed and, thanks to the persistence of one who notified Kunle’s family, he eventually received the medical care he needed to recover from severe depression.

For every Nigerian who finds this kind of support, millions more grapple silently with daily psychological challenges caused by job losses, mounting poverty, dashed hopes, or social pressures. Often, people are left feeling completely out of options, as noted by several community voices.

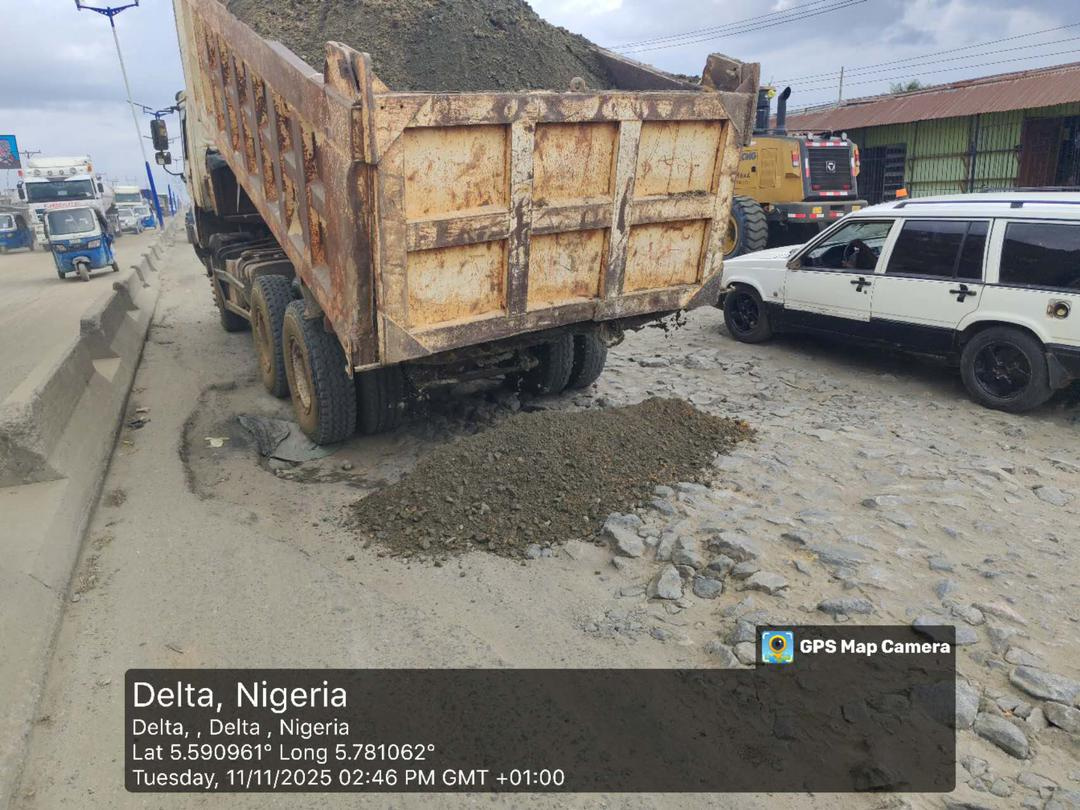

According to the World Bank’s latest Nigeria Development Update (June 2024), reforms like fuel subsidy removal and FX market liberalisation have yet to deliver equal economic benefits. Instead, the country’s entrenched structural inequalities, rising costs, and inflation now threaten even basic survival for many households. The bank further reported that the number of poor Nigerians has skyrocketed from 81 million in 2019 to 139 million this year, with projections that the absolute poverty rate could exceed 61 percent in 2025. From 2019 to 2023, average household consumption fell by 6.7 percent — a stark indication of declining well-being nationwide.

Against this backdrop, Nigeria faces a spiraling mental health emergency. Mental health facilities are seeing unprecedented numbers, with some reporting over a 200 percent surge in daily patient intake, according to facility reports. For context, the suicide rate reportedly doubled from 2020 to 2023, becoming a leading cause of death among Nigerians under 40.

World Mental Health Day, observed every October 10, arrives with particular urgency this year. Nigeria’s mental health infrastructure—threadbare and overburdened—is further weakened by the stark mismatch between professional capacity and public need. The Association of Psychiatrists in Nigeria (APN) currently counts only about 200 practicing psychiatrists for a population exceeding 220 million, with most based in urban centres.

Official estimates place the total number of psychiatric nurses at around 1,000, with approximately 319 registered clinical psychologists nationwide—far below the World Health Organisation (WHO) benchmark of one psychiatrist per 10,000 patients. The WHO also notes that mental health problems undermine productivity: depression and anxiety are responsible for about 12 billion lost workdays globally each year, costing economies up to $1 trillion annually.

In Nigeria alone, the economic cost of mental illness is believed to exceed N21 billion per year. Many families struggle with the escalating costs of medication, hospital care, and treatments—especially for conditions like schizophrenia, which often require long-term support.

Even when effective treatment exists, most of those affected cannot access it. Beyond costly care, many Nigerians face stigma, discrimination, and sometimes outright abuse, as discussed by local advocates. The barriers—high service costs, poor insurance coverage, limited infrastructure, and a severe shortage of professionals—have only widened the mental health gap.

The global situation provides sobering context: nearly one in seven people worldwide is living with a mental disorder, WHO data from 2021 shows. In Nigeria, these realities are compounded by insecurity, poverty, and dire social conditions.

Socio-Economic Stress and Insecurity: Major Drivers of Mental Health Crisis

Insecurity, unemployment, and armed robberies—not to mention persistently high inflation—are all intensifying Nigeria’s mental health burden, especially among youth and adolescents. Experts like Professor Taiwo Obindo, President of the APN, point to the impact of declining economic power, widespread joblessness, and underemployment as key contributors to rising rates of depression and substance misuse among young adults.

Obindo estimates that 85 to 90 percent of Nigerians living with mental health conditions are unable to access qualified care. Deep-rooted myths, prohibitive treatment costs, and a lack of proper facilities remain significant barriers. He also highlights the fact that, while the WHO recommends at least one psychiatrist for every 10,000 people, Nigeria’s ratio now stands at one psychiatrist per approximately one million citizens, with many trained professionals leaving for opportunities abroad.

Most psychiatrists are concentrated in urban areas, meaning the country’s predominantly rural population—over 65 percent—often relies on traditional or religious healers despite the lack of evidence-based care. “It is a cycle of being unable to access proper facilities due to cost and logistics, leading to reliance on unregulated traditional or faith-based practices,” Obindo explained.

He added that misconceptions around mental health are still widespread. The stigma attached to being labeled “mentally ill”—or even having a history of mental illness in the family—can hinder opportunities for marriage, employment, or social engagement. In some areas, those with severe conditions may be sent back to their villages and subjected to degrading treatment instead of receiving medical help.

Obindo calls for urgent action: fully implementing the Mental Health Act (gazetted in 2023), offering stronger incentives for healthcare professionals to remain in the country, and expanding the National Health Insurance Scheme to cover more aspects of mental health.

He stressed: “Integrating mental health into primary healthcare—intended as far back as 1996—still hasn’t happened. This is a critical gap.” According to Obindo, genetics, trauma, and poverty all intersect to shape Nigeria’s mental health crisis. “Poverty and mental illness are interconnected: people with mental health conditions are more likely to slide further into poverty, creating a downward spiral, especially in chronic cases.”

The Mental Health Policy Gap and Its Far-Reaching Consequences

Nigeria’s failure to fully implement its mental health policy does not only represent a humanitarian concern but also carries social, economic, and developmental consequences. For workers across the country, illnesses like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder impact concentration, energy, and reliability—leading to high absenteeism and staff turnover, which ultimately hampers productivity and income.

For children and adolescents, the effects are equally profound: school absenteeism, poor academic performance, and increased dropout rates, often deepest where poverty or conflict is most acute.

Dr. Olugbenga Owoeye, Consultant Psychiatrist and Acting Medical Director at the Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Yaba, emphasised that, “Limited facilities and weak health infrastructure leave millions without proper support. ‘Access to Services’ is the focus this year, especially during mental health emergencies.” Owoeye argues that every state should have at least one dedicated psychiatric hospital—a far cry from the current reality of just nine adult federal facilities for the entire country.

The 2021 National Mental Health Act, signed into law in early 2023, makes provisions for protecting human rights and integrating mental health into primary care, but the pace and scale of implementation remain major concerns. Owoeye highlights the urgent need to expand both insurance coverage and physical access to mental health services to remove financial and logistical barriers for patients.

“Many states lack a single psychiatrist. The shortage extends to clinical psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, and occupational therapists—each vital to a holistic mental health care system,” Owoeye explained. Continuous training and recruitment, he argued, are essential to closing these gaps.

Owoeye called for government investment in research centres focused on Nigerian mental health needs and reminded citizens to avoid drug abuse as a coping mechanism. “People turn to drugs to sleep or escape, but this only creates further problems. Regular exercise, rest, and positive community involvement—such as religious activities—can help support mental health,” he added.

Mental health challenges are not unique to Nigeria, but the consequences here are sharpened by poverty, insecurity, and the slow progress toward policy implementation. In places where conflict or hardship prevails—be it in Nigeria or elsewhere—the mental health toll can be devastating if left unaddressed.

What do you think is the most urgent step Nigeria should take to address the growing mental health crisis? Share your thoughts with us below and don’t forget to follow for more coverage on health, wellness, and local initiatives making a difference.

For general support or questions, reach out via support@nowahalazone.com.

Stay connected for updates—follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

Let your voice be heard. Your story matters!