In November 2023, several months after Uba Sani was sworn in as governor of Kaduna State, government officials gathered at Arla Farms in Damau for the much-publicized groundbreaking ceremony of a new dairy facility. This event was seen as a milestone in the state’s efforts to modernize local dairy production, drawing interest from farmers, agricultural experts, and key stakeholders alike.

Fast forward less than a year, and specific groups—including local farmers, veterinary students, and policy makers—were invited to preview what promised to be an impressive dairy operation. Attendees were shown sophisticated systems for animal care, modern feeding techniques, and the latest technology in milk production, all designed to boost efficiency and output while supporting community livelihoods.

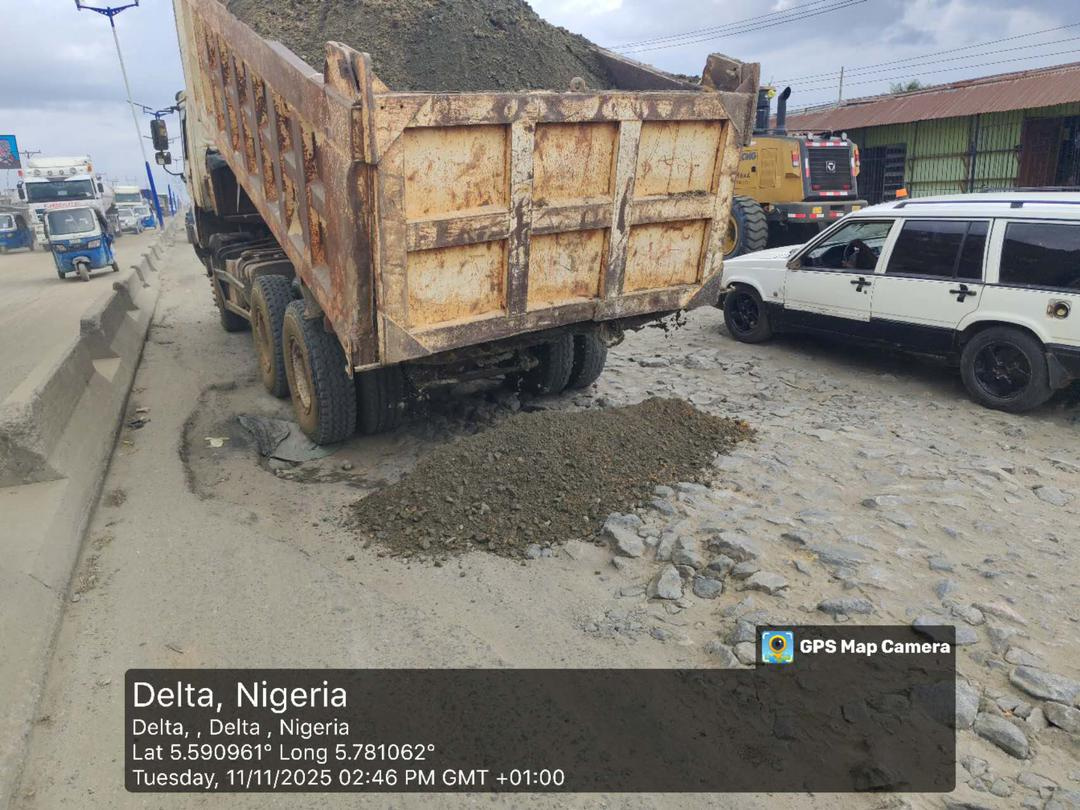

However, when a DUBAWA team visited the 400-hectare Damau site in February 2025, reality fell short of expectation. The only way in was a rough, untarred road lined with overgrown grass and roaming cattle, quite distant from the vibrant picture painted at inception.

“Money has already finished. I am telling you,” explained Abdulkareem Yahaya, a Damau local, to DUBAWA, addressing the stunted development at the site. According to Yahaya, critical shortages in funding caused many contractors responsible for core infrastructure—such as roads and drainage—to abandon their work.

Yahaya’s comments echo concerns shared on social media, such as by X user Happy Ustaaz, who claimed that out of the government’s initial N10.5 billion loan for the project, only 20 of the promised 1,000 farmhouses have been completed. DUBAWA sought to verify this and investigate the farm’s progress.

The Damau project traces its origins to January 2020, when the then governor, Nasir El-Rufai, announced its launch in Kadina’s Kubau Local Government Area. One of its major goals: to reduce conflict between herders and farmers—a recurring issue in Nigeria’s North, costing farmers significant losses and increasing food insecurity.

Designed as a 1,000-unit household dairy community, the Damau project was championed by the state in partnership with Danish firm Arla and the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association. Stakeholders saw it as a new model to address the root causes of rural conflict by offering structured settlements and sustainable income sources.

At the project unveiling, El-Rufai described it as a “sustainable answer” to the region’s security and agricultural challenges, with Arla pledging support for local capacity building and commercial-scale dairy operations in Nigeria. Peder Pederson, managing director of Arla Foods Nigeria, underlined the company’s commitment to both business and broader sustainability goals.

Tamar Nandul, the former head of Kaduna Market Development and Management Company (KMDMC), once provided local media with a detailed vision for the settlement. She outlined plans for three districts of about 1,800 hectares each, subdivided into clusters—provisioning both living space and arable land. Each intended beneficiary household would access five hectares (half for residence/gardening, the rest for fodder cultivation), as well as receive crossbred cows for milk production and breeding.

Despite Damau’s remoteness and limited infrastructure, the Kaduna government announced plans for 130 kilometers of new roads, 37 culverts, two bridges, 400 cattle sheds and calf pens, as well as education, health, and security facilities. Skills-building was another promised component, with Arla constructing a demonstration farm, including residential quarters, feed mills, and advanced milking systems. Initial investments totaled approximately $14 million, with promises of further expansion and new processing plants.

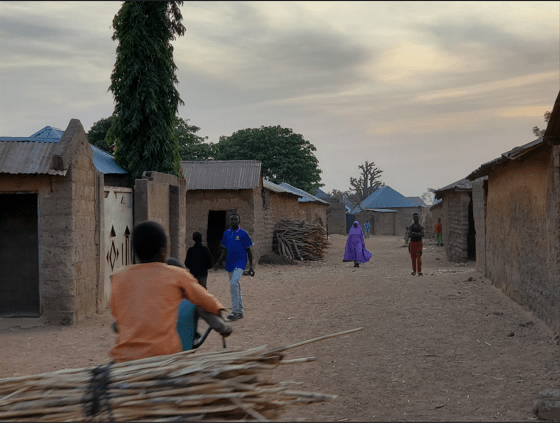

On a February visit, DUBAWA reporters described the village as shrouded in gloom. Damau had not had public electricity for over two decades—solar panels offered faint illumination. Residents described a slow-paced daily life, reliant on well water and basic farming for sustenance.

According to a local, Danladi Bello (an alias used for safety), the original plan under El-Rufai aimed for Damau villagers to be the first beneficiaries, considering their proximity to the project. Still, Nandul later clarified to NOWAHALAZONE that the full list of beneficiary farmers was to be drawn from across Kaduna State, including notable towns such as Makarfi, Hunkuyi, Soba, Zaria, and Sabon Gari.

Damau remains predominantly Fulani, with a strong tradition of cattle rearing. Due to delays, many reverted to open grazing to find enough feed, often trekking great distances and risking losses to cattle rustling—a longstanding threat in northern Nigeria.

Bello recounted to DUBAWA how the project team began by collecting basic information from interested villagers, promising opportunities in dairy farming. Later, 400 candidates were selected, grouped into ten cooperatives of 40 members each, with governance overseen by Kaduna State Cooperative Society. Those groups would then appoint leaders and form an “Apex body” for communication with project managers.

Although not all cooperative members owned cattle—some being primarily crop farmers—all were trained in dairy techniques. But according to Bello, the lack of promised imported cows remained a severe limitation, as local breeds yield far less milk than European Holsteins.

“The cows are not yet here… Our local ones produce only a litre per day. The ones Arla uses can give up to 25 litres a day,” he lamented, echoing widespread frustration with the project’s sluggish progress.

Bello also suggested that the transition between El-Rufai’s and Sani’s administrations hampered momentum, citing new appointments and a “lack of rapport” between beneficiaries and officials as obstacles to completion. He raised concerns that expressing dissatisfaction publicly could jeopardize any remaining government support.

To make ends meet, local families rely primarily on small-scale crop farming—a means of survival, but not prosperity. Bello emphasized that if the government had delivered as promised, villagers could have improved their livelihoods, with profits from milk production increasing their spending power.

Another resident, Sabiu Damau, reported that after four years of engagement, participants were taught modern husbandry and feed cultivation methods. Yet, facilities such as the new homes, schools, and commercial centers remain unfinished and inaccessible.

“They taught us how to feed cows… but even though they built about 200 houses, none are complete,” said Sabiu, the cooperative secretary.

DUBAWA’s visit confirmed around 30 completed buildings and five abandoned cattle pens. No new schools, markets, or clinics had been built, leaving villagers dependent on makeshift stands and temporary solutions.

Despite repeated assurances since 2022 about land and infrastructure, Sabiu claimed that the only tangible support received has been small sums—mainly stipends at workshops—rather than meaningful investments or resources.

Workshops have been held five times, often with only group representatives present. Danish partners occasionally request meetings in Lagos to check on resource distribution, but substantial results remain elusive. Many trace the standstill to the 2023 change in state leadership, which also marked the falling out of former allies El-Rufai and Sani.

As Sabiu shared, “It (the programme) stopped. They told us not to worry, that it was a temporary setback.” However, three years later, the project was still stuck in its initial phase: only Damau’s natives had so far benefited, with just 400 out of the planned 1,000 farmers involved.

Arla’s corporate project manager, Funmi Oduntan, told DUBAWA that Arla’s role is to train farmers once the state has settled them on the site. The farmers, she explained, would eventually access the demonstration farm for practical training and milk production, with Arla acting as the exclusive milk offtaker—an arrangement intended to boost local revenues.

Currently, Arla provides training with support from groups like the Milk Valued Chain Association, though physical access to demonstration farms remains rare. Farmers are brought on open days to see Holstein cows and processing equipment, but have not received the promised high-yield cattle.

“It is not just theoretical—they practice with their own cows, even if those cows do not yield as much milk,” said Oduntan. According to her, housing and pasture must be completed before farmers will be officially relocated and the full benefits unlocked. “It is in progress; it is not completed yet,” she added.

When contacted, Kaduna State Government’s spokesperson, Ibrahim Musa, indicated he was newly appointed and not familiar with the dairy project, promising to follow up—but as at the time of reporting, there was no update. Efforts to reach former El-Rufai aide Muyiwa Adekeye also yielded no response, nor did inquiries to the Ministry of Finance about project funds after two months.

The situation in Lere Local Government paints a similar picture. Cattle owners like Adamu Maigari, who started rearing cattle in 2019, continue traditional open grazing. According to Maigari, after daily grazing in the bush, the cows are returned to the village by evening, with local authorities allowing the practice and some crop farmers benefiting by feeding cattle on post-harvest crops.

Yet, Maigari and other herders were unaware of the Damau project. “I have told you, I don’t even know this Damau household milk farming. There are many cattle rearers who don’t know,” he said. This disconnect was also observed in Sabon Gari, where intended beneficiaries remain largely uninformed about the initiative’s existence.

Are you affected by government projects like this or have your own story from Kaduna, Nigeria, or elsewhere in West Africa? What do you think about the future of state-backed agricultural programmes, and how could they work better for local communities? Drop your thoughts in the comments below and follow us for continuous updates.

Do you have a valuable news tip, community story, or lived experience you want to share or even sell? We want to hear from you! Email us at story@nowahalazone.com to get your story featured or discuss possible story sales. For support and inquiries, reach us at support@nowahalazone.com.

Stay connected with us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram for more local news, analysis, and feature stories!