The call for stronger policies that champion gender equity and better access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services has become a pressing matter in Nigeria, as highlighted by leading health professionals at the 2025 Gatefield Health Summit held in Abuja. The challenges facing Nigerian women in accessing these critical services mirror issues playing out across West Africa, placing the spotlight on the urgent need for action from policymakers, health sector stakeholders, and communities.

At the summit’s panel discussion, titled ‘Women at the Centre: Advancing Gender Equity in Health,’ experts warned that the twin challenges of entrenched cultural barriers and inadequate health infrastructure threaten the health and empowerment of women across the country. Limited government funding was cited alongside these hurdles as a major reason why many Nigerian women remain underserved in the area of sexual and reproductive health.

Kolapo Oyeniyi, a respected public health specialist based in Lagos, argued that sexual and reproductive health cannot continue to be treated as an isolated concern, separate from the country’s core healthcare strategy. “Sexual and reproductive health is not just about preventing unplanned pregnancies or treating infections; it covers physical, emotional, and social well-being for both women and men,” Oyeniyi emphasized, underscoring his comments with reference to World Health Organization definitions.

He further clarified that while gender equity focuses on removing systemic barriers to give all genders a fair playing field, genuine empowerment of women is what ensures these changes translate into real improvements in daily life. “We can advocate for fairness, but unless women are empowered—through education, economic opportunity, and access to healthcare—equity remains out of reach for many,” he explained.

Why Access Remains a Challenge

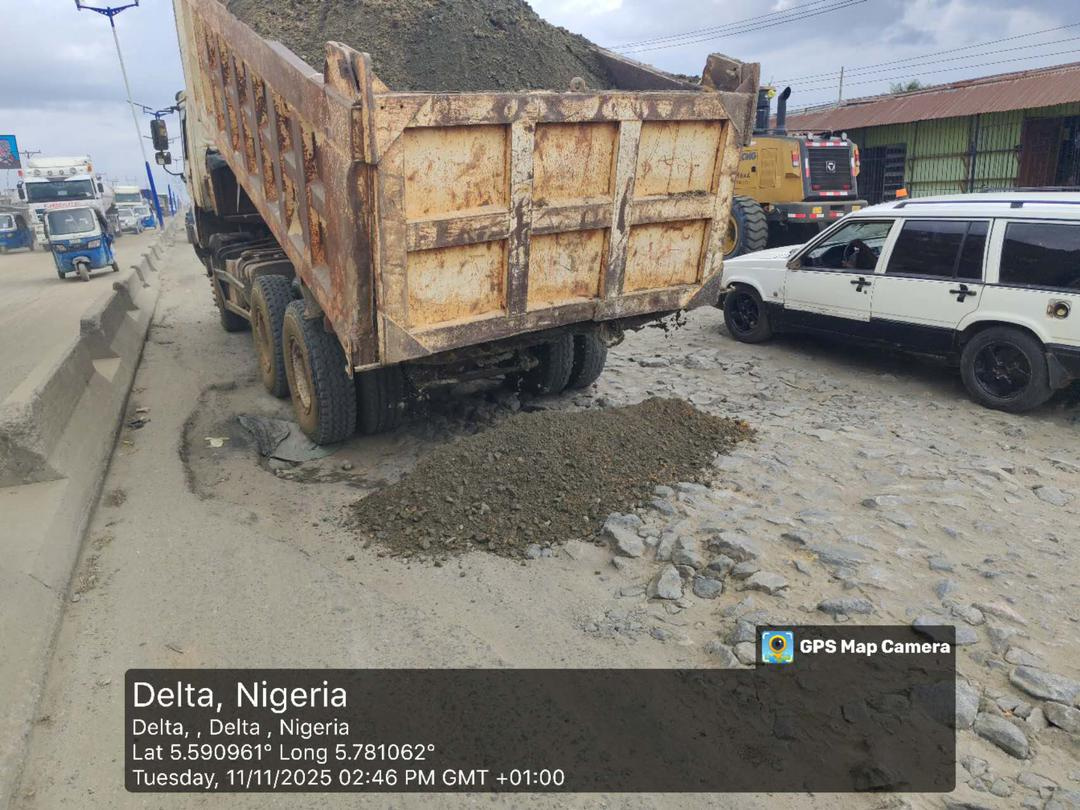

Oyeniyi voiced concern about the operational limitations faced by primary healthcare centres. In numerous Nigerian communities, these facilities operate on restricted schedules, often closing as early as 2 p.m. or 4 p.m.—creating access gaps for those needing care outside conventional hours. This is particularly problematic for working women, rural residents, or young people who cannot easily reach clinics during daytime hours.

Beyond limited hours, Oyeniyi pointed to a more systemic issue: the shortage of trained health personnel. Many clinics lack staff capable of providing long-term contraceptive services, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants. This, combined with restrictive abortion laws and powerful cultural taboos, makes it even more difficult for women to manage their reproductive health needs responsibly and safely.

“We cannot hope to make real progress unless we address these bottlenecks and get accurate, reliable data to guide our policies,” Oyeniyi stated, adding that social norms—such as early marriage and the stigma surrounding family planning—continue to undermine advancements across communities.

Another barrier identified is the limited engagement of men in SRH initiatives. “In many Nigerian homes, men are the primary decision-makers. When they’re not actively engaged or supportive, women face persistent challenges in seeking the care they need,” the public health expert observed.

To address these challenges, Oyeniyi called for targeted strategies aimed at involving men as partners and advocates for women’s health. He recommended a three-pronged approach: robust male engagement, comprehensive community education to combat harmful norms, and significant investment in healthcare worker training and digital technology. “Service delivery must be modernized, with well-trained, well-equipped providers who can work in tandem with community expectations,” he said.

Integrating Health Services: A Smarter Approach

Olufemi Ibitoye, Technical Advisor with Pathfinder International Nigeria, brought another dimension to the conversation. He argued for the integration of SRH services with other essential healthcare offerings to address inefficiencies and ensure more holistic care. According to Ibitoye, the prevalent strategy of training select healthcare workers on narrow interventions can backfire if those individuals move on or are unavailable. This siloed approach, he noted, often leads to coverage gaps, especially in remote or resource-constrained areas.

“It is not sustainable to keep training healthcare workers in isolation for one service each,” Ibitoye said. “Instead, we need a system where every provider is able to offer multiple essential health services. That’s how we’ll close gaps and ensure no one falls through the cracks.”

He also raised the issue of accountability in the management of resources across the Nigerian health sector. Ibitoye noted that without strict oversight, resources earmarked for SRH can easily be mismanaged or wasted, resulting in poor health outcomes for women and families.

To push the conversation forward, Oyeniyi recommended a pragmatic solution: integrating SRH services into clinics that already handle non-communicable diseases (NCDs)—such as diabetes and hypertension. “By offering reproductive health services alongside NCD care, we reach not just young women but also men and older adults who regularly visit these clinics. This integration would dramatically broaden our impact,” he explained.

He added that such a strategy could also confront misconceptions around menopause, family planning, and sexual health that persist in many Nigerian and West African communities. According to him, a more holistic approach encourages continuous learning and openness, especially as taboos around such conversations gradually fade with consistent education and outreach.

The Broader West African and Global Context

Gender equity in health is not just a Nigerian issue. Across West Africa, similar challenges persist, with millions of women encountering deeply rooted gender norms and insufficient access to essential health services. Nigeria’s struggle is emblematic of a broader continental push for reforms that also affect Ghanaians, Ivorians, and citizens across the region. Reports from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and various Ministries of Health indicate that early marriage, high fertility rates, and unmet contraceptive needs are regional challenges requiring urgent attention.

Globally, there is increasing recognition that gender equity is pivotal for sustainable development. International health agencies—including WHO and UNFPA—support evidence-based programs that empower women and engage men, recognizing that improvements in one country can serve as a template for neighboring states. Nigeria, with its large population and influence, is positioned to lead by example in championing rights-based, people-centered healthcare reforms.

Local Perspectives and the Way Forward

Many local advocates echo the sentiments of Oyeniyi and Ibitoye. For example, Sarah Musa, a midwife in Kaduna, notes, “The women I see every day want to make the best decisions for themselves and their families, but often cannot due to stigma or lack of service availability. Engaging local leaders and community influencers holds the key to lasting change.” Materials from agencies such as the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) reinforce these views, emphasizing that community buy-in and public education are necessary to shift lasting attitudes.

It is clear that meaningful progress will demand a combination of political will, increased funding, policy reforms, and continued community-level dialogue. Advocates call for bipartisan government action to prioritize healthcare spending, targeted interventions for underserved groups, and the integration of local customs into health policies in a way that respects cultural realities while advancing gender equity.

In conclusion, the road to achieving gender equity in health in Nigeria—and across West Africa—will require innovation, persistence, and cooperation between government, civil society, healthcare providers, and communities themselves. It also calls for the active involvement of men as allies in the movement to empower women and improve family health. Real change is possible when every voice is brought to the table and every policy is implemented with the needs of the most vulnerable in mind.

How do you think Nigeria and other African countries can accelerate progress in providing equitable health services for all? What changes would make the biggest difference in your community? Drop your thoughts in the comments and follow us for more on health reforms and gender equity.

For general support, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Join the conversation—follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram for the latest updates on health, gender, and community stories across Nigeria and West Africa!