The World Trade Organisation (WTO) Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies is poised for adoption this year, with Ghana standing out as the latest African nation to ratify the deal. Currently, 102 countries are officially on board, and just nine more ratifications are needed to hit the magic number of 111 that will set the treaty in motion. If this milestone is reached, the agreement will come into force in what experts are already calling a potential ‘super year’ for ocean governance. For Nigeria and its West African neighbors, this could mean a significant shift in both economic and environmental prospects along the coastline.

Despite its importance, only about a third of African states have ratified the treaty, raising concerns about its effectiveness where change is most needed. The slow pace of ratification is drawing attention not just from policymakers but from local fishing communities who depend on sustainable marine resources for their daily livelihoods and national food security.

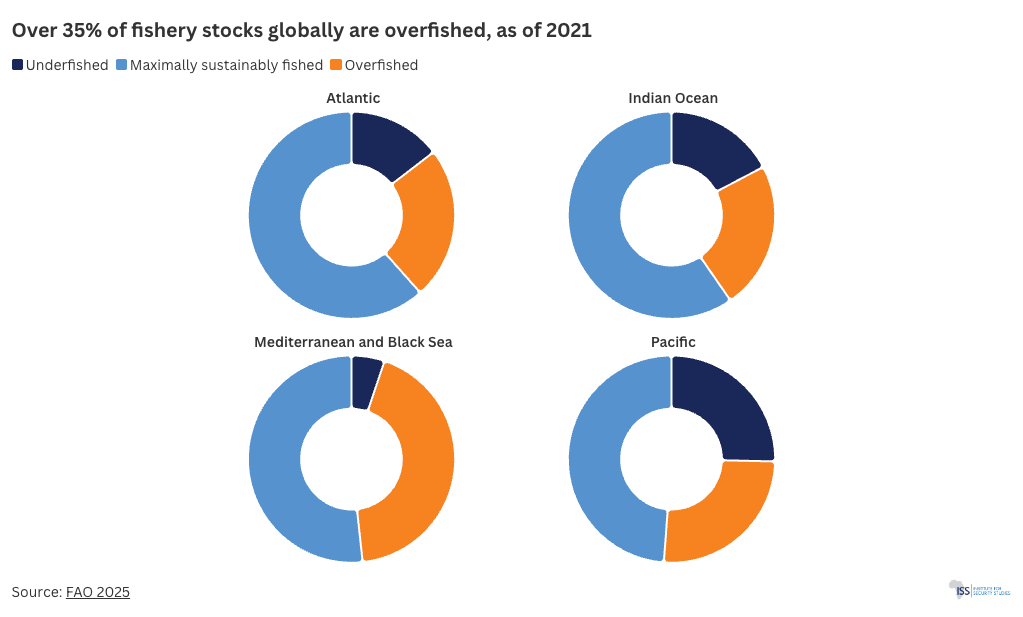

The issue is especially pressing for Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, and other coastal West African countries. As highlighted in the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s recent State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report, Africa’s fisheries are currently some of the most vulnerable in the world. Overfishing and illicit, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing have devastated marine stocks, with only a small fraction of catches harvested at sustainable levels. The impact is felt most by the millions of Nigerians who rely on fresh fish as a vital protein source.

Africa’s challenges can be summed up as a triple threat: foreign subsidized fleets that deplete stocks, fragile systems of ocean governance, and the looming threat of climate change. According to Lagos-based fisheries consultant Oladipo Amusan, “Small pelagic fish stocks along West Africa have already collapsed in some places, while East African coral reef fisheries are producing less than sustainable yields. For coastal communities, these trends jeopardize food security and local jobs.” These concerns resonate across Nigeria, where many small-scale fishermen have reported dwindling catches and competition from industrial trawlers, some operating illegally.

Currently, estimates suggest that illegal exploitation robs Africa of at least $11.2 billion in revenue annually. For Nigerian authorities, this means lost tax revenues and increased pressure on coastal communities facing poverty. The WTO agreement aims to clamp down on unlawful fishing practices and harmful subsidies that incentivize overfishing, providing hope for change across the region.

Globally, records show 102 nations have ratified the deal, with several others—including Ghana—having completed their internal processes but awaiting full recognition due to pending formalities. Nigeria has expressed interest, but as of June 2024, is yet to formally deposit its ratification instrument with the WTO. According to trade officials in Abuja, “internal consultations are ongoing, and relevant agencies are being briefed on the technical requirements.”

The agreement itself targets three core problem areas that drive the depletion of marine resources, rolling them out in two stages. First, it bans subsidies that facilitate the exploitation of already overfished stocks and aims to boost conservation efforts, especially in regions where regulatory frameworks are weak.

Second, it blocks fishing subsidies in high seas territory, outside the authority of regional fisheries bodies, where enforcement often fails and migratory species are particularly vulnerable. And finally, any fishing vessel that has engaged in illegal activities will be ineligible to receive subsidies. This structure is designed to address the root causes of overfishing and illegal activity—concerns long voiced by environmental groups and local fishermen alike.

These measures attempt to answer persistent complaints that global fisheries subsidies—often provided by wealthier foreign governments—enable distant-water fleets to operate off West African coasts and outcompete local artisans.

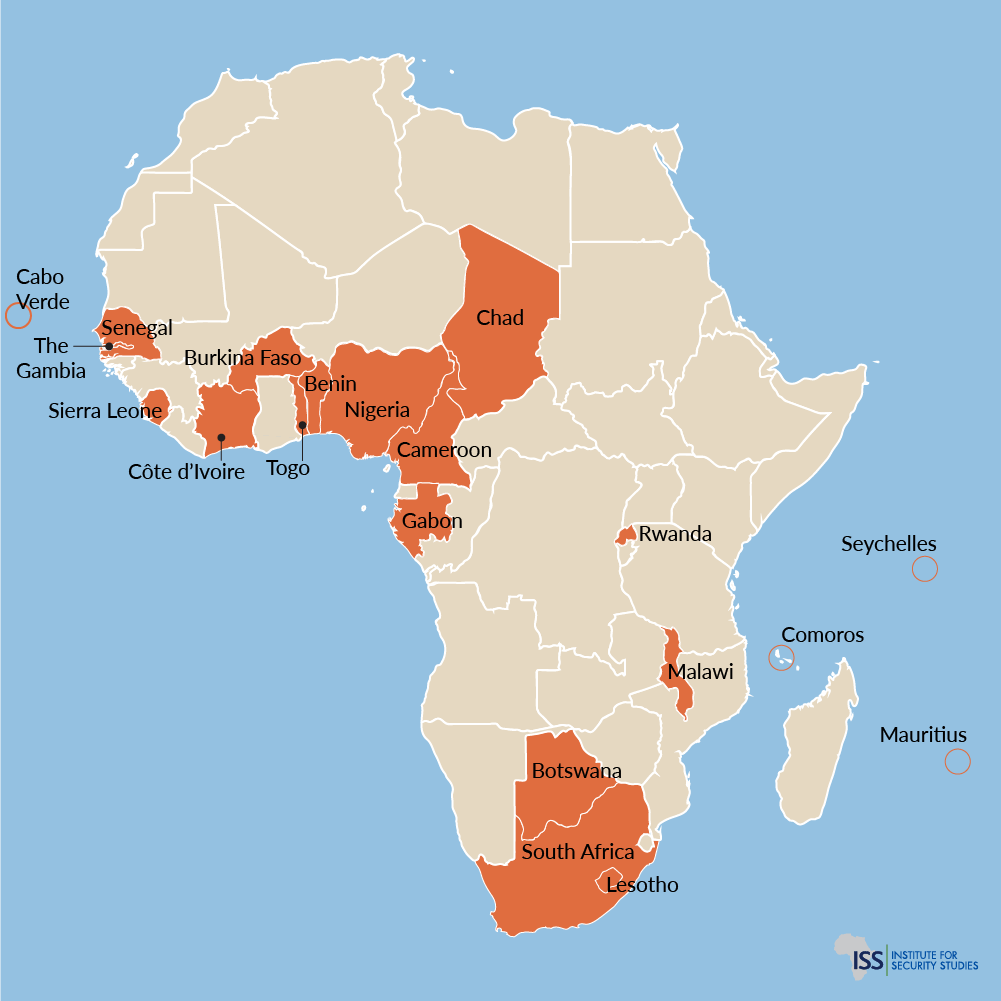

Despite clear potential benefits, support on the African continent remains lukewarm. According to the WTO, only 20 African countries have officially ratified the agreement. Notably, most support has come from West Africa, where the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has actively urged its members to endorse the initiative. Nigerian officials have acknowledged that more public education and inter-agency collaboration are needed to spur action.

East and Southern Africa show even less engagement, with just four coastal countries—Comoros, Mauritius, Seychelles, and South Africa—having completed ratification. A likely explanation is the agreement’s focus on trade, rather than strictly environmental or fisheries management, meaning implementation cuts across multiple ministries, including Trade, Environment, Fisheries, and Foreign Affairs.

Nonetheless, momentum appears to be building for the agreement’s entry into force before year’s end, making Africa’s preparedness for implementation more critical than ever.

Implementation may prove resource-intensive, especially for developing economies like Nigeria’s. Signatories must compile comprehensive inventories detailing the scale, recipients, and purposes of existing fisheries subsidies. This effort requires sophisticated coordination between government bodies, political will, and investment in digital reporting systems—challenges that Nigerian officials admit will likely require support from international partners.

According to maritime security analyst Chukwuma Obasi, “A failure to build capacity or the political resolve to enforce these provisions could turn countries like Nigeria into easy targets for illegal fleets. The effectiveness of this agreement hinges squarely on our ability to enforce it on the ground.”

Enforcement doesn’t happen automatically. Prohibitions under the agreement are triggered when a party—be it the coastal nation, the flag state of a vessel, or a relevant regional fisheries management organization (RFMO)—identifies and pursues a breach. However, there are concerns about the capacity and willingness of such groups to act swiftly and effectively.

RFMOs, for example, aren’t always equipped to combat illegal fishing, and member states sometimes prioritize short-term profit over robust enforcement. Flag states offering ‘flags of convenience’ are also rarely motivated to crack down on their revenue sources. As a result, success hinges on local vigilance and the collection of credible evidence—a challenge for many countries where resources are limited.

Rather than dampening enthusiasm for reforms, these obstacles highlight the scale of work ahead for countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and their neighbors if they are to maximize the deal’s benefits. So, how can West African states make this agreement work for them?

Action Points for Africa’s Coastal States

- Use the WTO’s self-assessment system to review and align domestic policies with the treaty’s demands, including identifying laws and institutional gaps. Technical assistance may be essential here.

- Strengthen cooperation between fisheries, trade, and finance ministries to ensure smooth implementation, accurate reporting, and transparency regarding subsidies and conservation actions.

- Take advantage of the WTO Fisheries Funding Mechanism, which provides vital resources for developing countries to modernize their management systems, improve law enforcement, and help local fishers adopt sustainable practices. Access to these funds kicks in after ratifying the agreement.

But observers warn: this deal is not a cure-all. It is a promising tool, but its impact will rely on West African countries’ collective commitment to improved maritime security, governance, and the full implementation of international measures such as the UN Port State Measures agreement.

Practical steps like more effective surveillance, stricter port inspections, and deeper regional cooperation are essential to curbing illegal catches and discouraging foreign fleets from bypassing local rules. In a region where fish remains a dietary staple and a vital source of income, failing to act could threaten not just food security, but the stability of coastal economies.

In summary, while the WTO Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies offers a pathway to protecting marine resources and restoring livelihoods across Nigeria, Ghana, and beyond, its success will rest on decisive local action, transparent policy, and robust enforcement.

(This article was first published by ISS Today, a Premium Times syndication partner, and is reproduced with permission.)

What’s your take on the WTO fisheries deal? Do you think Nigeria and West African countries are ready to enforce these crucial new rules? How might these changes affect communities along our coastlines? We want to hear your views—drop a comment below and join the conversation.

Have a story, news tip, or expert opinion on maritime security, fishing, policymaking, or the blue economy? Want your story featured or to sell your exclusive?

Email us at story@nowahalazone.com and let’s put your story on the map!

For support inquiries, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Don’t miss out—follow us for daily updates on Nigeria and Africa’s biggest news at Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram!