A heavy, almost tangible silence now drapes the Memorial Arcade and Garden in Lisa Town, Ogun State. Despite faint signs of recent weeding, the grounds have an air of neglect—overgrown bushes, faded paint, and cracked walkways tell their own story. The main arcade, constructed jointly by the Federal Government and Ogun State, is a shadow of what was once envisioned as both a place of rest for crash victims and a notable national monument.

Many nameplates once attached to gravestones have broken off or disappeared, denying even the basic dignity of remembrance to those lost. The structure’s physical decay—sagging ground at the entrance, accelerating cracks at the rear, and a billboard now collapsed beneath thick weeds—stands as a testament to years of official neglect.

Originally built to commemorate one of Nigeria’s most painful aviation tragedies, the arcade’s radiant promise has faded. Reports indicate the site was last repainted over a decade ago by a now-defunct airline. Today, peeling paint and crumbling walls bear witness to how quickly national remembrance can slip into abandonment.

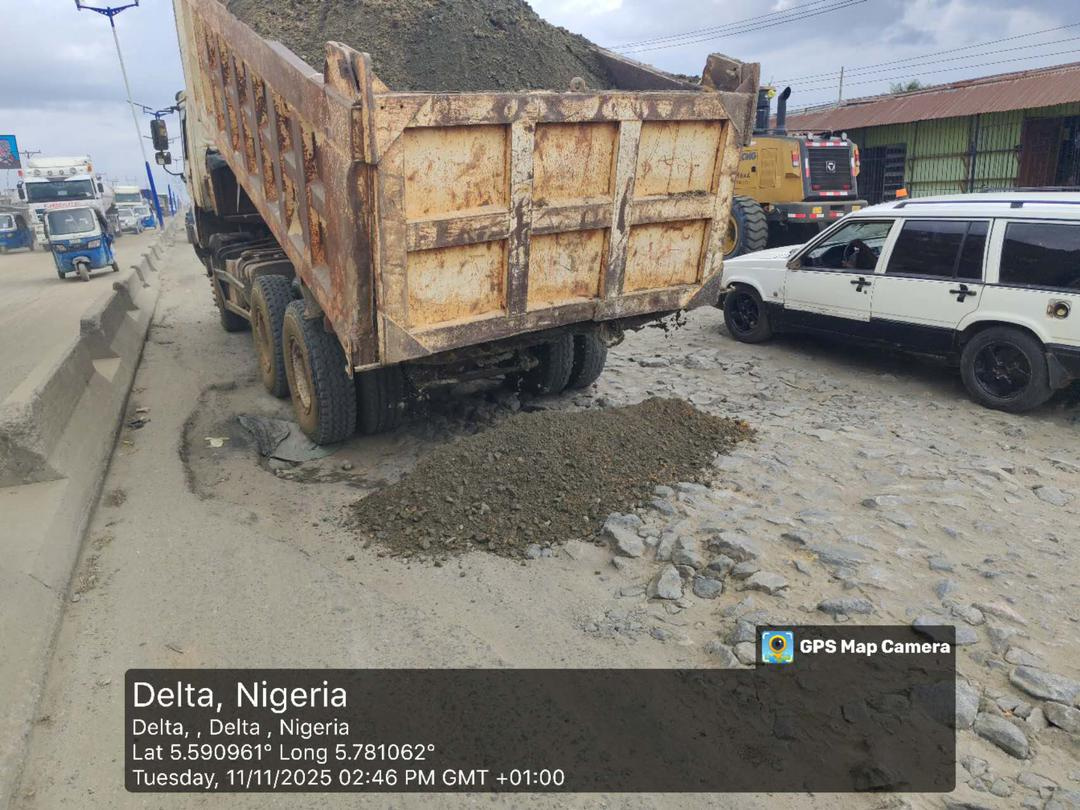

Accessing the site is itself a formidable challenge. The once-paved road, constructed soon after the fatal crash, has all but disappeared, eroded by seasonal rains and neglect. Deep ditches now mar the path, making it almost impassable for vehicles, with only determined commercial motorcycle (Okada) riders charging hefty fares to navigate the winding, broken terrain. During a recent visit, visitors noted the harrowing condition, with stuck vehicles lining the road and Okada men themselves struggling to pass.

According to residents and local officials, much of this decline set in just months after the initial construction works, with the rainy season accelerating the deterioration. The annual memorials, once observed with fanfare, have faded alongside any consistent governmental presence.

Remembering the 2005 Bellview Crash

On October 22, 2005, Nigeria was plunged into collective mourning after Bellview Airlines Flight 210, a Boeing 737-200, crashed into Lisa Town, killing all 117 onboard. The tragic loss rippled beyond the country’s borders, drawing both regional and international mourning. Flight 210, carrying 111 passengers and six crew, departed Murtala Muhammed International Airport, Lagos, for Abuja, before disaster struck minutes after takeoff.

Investigators, including the Nigerian Accident Investigation Bureau, reportedly found no survivors and described the violence of the impact: the plane struck the ground vertically at tremendous speed, leaving few recoverable remains. The crash instantly drew attention to issues of air safety and oversight, not just in Nigeria but across West Africa. International passengers, including Ghanaians, Malians, Britons, Gambians, and others, were among those lost. U.S. authorities confirmed the presence of one American soldier, further deepening the international scope of tragedy.

High-profile Nigerians—such as Waziri Mohammed (Nigeria Railway Corporation Chairman), Maria Sokenu (former Peoples Bank Managing Director), and others—were listed among the deceased, compounding the national trauma. The cockpit was crewed by highly experienced Nigerian pilot Captain Imasuen Lambert, Ghanaian first officer Eshun Ernest (whose wife was also aboard), and engineer Steve Sani. Notably, Captain Lambert had a long career with a twelve-year hiatus due to an earlier armed robbery injury, according to the official report.

There was significant confusion and anguish in the aftermath. Early reports mistakenly suggested survivors, which proved false and heightened the nation’s heartbreak. Investigation faced serious hurdles: the black boxes were never found and the crash’s severity, along with alleged site looting, left little physical evidence—delaying the final official report until 2013. As a result, the precise cause of Flight 210’s crash remains undetermined.

A Memorial Now Forsaken

Shortly after the accident, the Federal Government and Ogun State commissioned the Lisa Memorial Arcade and Garden, both to honour the victims and anchor the memory of that dark day. For a few years, the site attracted visitors from across Nigeria, including school groups and the bereaved, and was briefly heralded as a burgeoning local tourism site.

However, as community leaders like Chief Adeyinka Adefunmiloye (Amona of Lisa) explained, these gains quickly unraveled. Fewer families now visit, with many deterred by the unreliable, mud-filled access road. The existing guards, once paid by government, now rely on the local monarch’s generosity. “This place has been abandoned,” Adefunmiloye lamented. “Even the weeding is left to volunteers, as all official support has stopped.” According to the chief, repeated efforts to draw government attention—including appeals to the Nigerian Tourism Development Corporation and ministries at state level—have yielded only broken promises and brief official visits.

The physical environment mirrors this neglect: wild bushes crowd the entrance and climb the fences, and what remain of the once-orderly tombs are succumbing to erosion and overgrowth. Without regular care, what should be a proud memorial is slowly reverting to bushland.

Even local commerce tied to the site has suffered. The Okada riders—who used to ferry a steady flow of visitors and mourners—now rarely venture to the area. The years of neglect have meant what was once a busy, purposeful place has fallen silent.

Local Voices: Community Outcry and Activism

In the days leading up to the 20th memorial anniversary, groups like the Ifesowapo Consultative Forum—a coalition of 32 surrounding communities—attempted to organize thorough commemorations, reportedly planning inter-religious prayers, safety lectures, and outreach for affected families. Dr. Fola Abati, chairman of the forum, emphasized the need for remembrance to inspire progress. “It is about using history to inspire progress. We owe it to the victims,” he noted, urging for renewal rather than sorrow alone.

Despite these intentions, recent visits found the site empty. From The Guardian’s observation, no government officials, family members, or local dignitaries attended the 20-year anniversary event—with only the arcade’s unpaid guard eventually appearing.

The sentiment among community members is one of resignation and growing frustration. Mrs. Victoria Olumekun, whose husband perished in the crash, has reportedly stopped visiting, discouraged by road conditions. Others attribute the waning attention not just to physical neglect, but emotional exhaustion in the absence of sustained public commemoration.

Elder Ikechuckwu, the arcade’s guard, detailed the extent of the abandonment: over a year with no salary, and all bush clearing now done by local youth volunteers. “Nobody comes anymore. Even the families do not visit,” he said, offering a stark snapshot of the site’s disrepair.

Otunba Segun Showunmi, a vocal community advocate, recently called on the Federal and Ogun State governments to urgently restore both access and dignity to the Lisa site. “Lisa Village… should be a national monument of remembrance,” Showunmi insisted. “The government must take responsibility by clearing the area, paving the road, and ensuring the place is preserved as a heritage site for reflection and learning.” He further urged collaborative partnerships with aviation stakeholders, civic groups, and local authorities to redevelop Lisa as both a memorial and a center of research on air safety.

Oba Najeem Oladele Odugbemi, the Onilisa of Lisaland, echoed these pleas, recalling how initial memorial intentions—including hospitality centers and expanded facilities—were abandoned almost as quickly as construction began. “We are appealing to both the Federal and State Governments to restore this important site,” the monarch stated. He noted the road is “impassable,” especially during the rains, and the unfulfilled promises of tourism-driven development under prior administrations.

Lisa’s memorial arcade, inaugurated by then-President Obasanjo and then-Governor Daniel, once symbolized collective national sympathy. Today, its battered tombstones and eroded structures are distressing reminders of promises unmet.

The tragedy brought fleeting attention to the small town, sparking a modest infrastructure upgrade in the immediate aftermath and making Lisa a temporary pilgrimage spot for the bereaved and for curious Nigerians and West Africans. But, two decades later, Lisa’s story is one of decay—a cautionary tale of memory slowly being erased by time, weather, and the limits of political will.

Lessons and Next Steps: Preserving National Memory

The Lisa crash memorial raises urgent questions about national approaches to tragedy and collective memory in Nigeria and across the region. What responsibility do federal, state, and local authorities bear in maintaining such sites? What is the role of civil society in sustaining meaningful commemoration? And how can memories of loss be transformed into opportunities for reflection, learning, and reform—especially in crucial areas like transport safety?

Stakeholders and experts like Lagos-based heritage analyst Funmi Alao assert that “sites like Lisa should be protected through dedicated funding, official policy, and collaboration between government and affected communities. Neglecting them risks erasing hard-learned lessons that could save lives in the future. Countries like Ghana and South Africa have enacted such policies for major memorials—Nigeria must do the same.”

As Nigeria and its West African neighbours continue to grow, prioritizing remembrance at sites of national tragedy isn’t just about honoring the past—it’s also about affirming the value of human life and encouraging progress.

What do you think should be done to ensure the Lisa crash memorial and similar national tragedy sites are maintained for generations to come? Share your thoughts below and let us know what changes you’d like to see from the government or local communities. For more in-depth stories and updates, follow us—and join the conversation.

Have a story to share or sell? We’re always listening. If you have a tip, personal reflection, or want to highlight an issue in your community, email us at story@nowahalazone.com to get your story published or discuss story sales.

For general support or to provide feedback, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Be part of the conversation: drop a comment below, and follow us on

Facebook,

X (Twitter), and

Instagram for more local stories and updates!