On a cloudy Tuesday in June, Monday Nweze headed to his farm in Ndiebor community, Ezza Inyimagu, Izzi LGA of Ebonyi State, with one task in mind: tackling the overgrown grass. Instead of the traditional cutlass, he opted for several litres of herbicide, specifically a product called “uproot,” loaded into his backpack sprayer. This routine has become second nature, not just for Nweze but for many farmers in the area.

Wearing his sprayer but lacking any personal protective equipment (PPE)—not even a face mask—Nweze worked with little concern for the direct impact on his health. “Not many farmers here wear protective gear,” he shared. Agrochemicals have become the go-to solution for controlling weeds and pests, especially across his two hectares of rice farmland.

However, this practice poses serious risks. Nweze recalled a frightening experience a decade ago: “I was poisoned by pesticides while on my farm in 2012. My health was failing daily until I was hospitalized. The doctors later told me to cover my nose and skin while using agrochemicals.”

Despite that health scare, Nweze continues to apply herbicides with little protection. He attributes his endurance to his body having “adjusted” to the newer, allegedly weaker agrochemicals. “Before, if you sprayed, even the wind would carry it and harm crops across the field. Now, though, I still take medicine after spraying—often I get catarrh, sometimes even malaria. These chemicals are terrible; even earthworms, which help with soil fertility, have disappeared from my land,” he noted, lamenting the broader environmental consequences.

Asked why he still uses herbicides, Nweze explained that hiring labourers is simply not affordable. “To clear even a portion of land, I’d need to pay N14,000. With N1,500, I can buy enough herbicide to spray the whole place, making rice farming possible for many who previously could not afford it.” He admitted that organic methods, like shifting cultivation, are better for the land, but said land scarcity has forced farmers to abandon such practices. “We used to rotate fields, but now, there is just not enough land.”

Nigerian farmers across the country are increasingly dependent on agrochemicals to boost productivity, largely because these inputs make clearing and protecting farmland more affordable and faster. Yet, there is an urgent need for awareness about the environmental and health fallout linked to these chemicals. Studies have associated repeated exposure to pesticides with a rise in cases of cancer, cardiovascular disease, skin issues, birth defects, immune impairment, and other illnesses. International agencies have further linked pesticide use to troubling health trends.

“Agrochemical poisoning can result in loss of life,” explained Prof. Tanimola Akande, a public health expert, in an interview in July 2023. According to the Pesticide Action Network, a global coalition, smallholder farmers and their families are at highest risk of pesticide-related conditions, including cancer and neurological disorders. Although Nigeria lacks centralized data on deaths from agrochemical use, local reports cite at least 270 fatalities in Benue State in 2020 caused by pesticide contamination in a river. Additional research by Nigerian NGOs recorded 454 deaths from 24 separate farm chemical poisoning incidents between 2008 and 2022, including among pregnant women and children.

Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates roughly 220,000 annual deaths from pesticide poisoning, with most cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries.

For some, agrochemicals are both blessing and curse. Ogochukwu Mbam, a rice and cassava farmer from Ndiebor, uses PPE each time he sprays, but he still commonly experiences nasal irritation and body weakness after exposure. “There’s no way to escape it—you inhale chemicals, and it affects your health. Sometimes, the impact even lingers, making you feel anxious about your own safety,” the young farmer, managing over four hectares, reported.

Beyond the health effects, Mbam notes decreased crop yields. “Weed and pest control are easier now, but farming was more rewarding before—soil nutrients have dropped. Crops grow better on land where we used to weed by cutlass, without agrochemicals.” He sees organic methods as safer health-wise and better for productivity, but a shortage of labour and high pay drive reliance on herbicides and pesticides.

Ngozi Uguru, a cassava and yam farmer from Abofia-Mgbo Agbaja, experiences burning sensations after spraying without protection, turning to herbal remedies for relief. Initially unaware of the risks, she soon learned the hard way that chemical exposure endangers not just her health but her crops and community. Her brother-in-law, Friday Uguru, recounted a tragic episode from 2012–2013: “People died after vegetables grown with agrochemicals were used in food. Survivors were few.”

According to her family, beneficial organisms like earthworms and centipedes are now rarely seen—organisms crucial for maintaining healthy, fertile soil have vanished due to repeated pesticide use. “These insects used to make farming easier, but they are no longer there,” he said.

Chijioke Agbo, recognized as the largest farmer in Obeagu Awkunanaw Community, Enugu State, depends solely on agrochemicals for weeding and pest control, eliminating the need for hired help. Yet, he too suffers health effects: “Every time I spray, the breeze carries the chemicals onto my skin, causing days of itching. Not even palm oil or vaseline helps the irritation.”

Despite knowing the risks, Agbo is driven by necessity—with labour costs climbing and persistent pest attacks, he feels he has little choice. In contrast, fellow farmer Chioma Oje has yet to report any ill effects, but admits, “I’ve learned it’s best to let some time pass after spraying before harvesting.” Researchers and health professionals warn that chemical poisoning may manifest immediately or over time, depending on exposure level and chemical type.

At Okwadike Care Hospital in Enugu, medical lab scientist Nkechi Okolie explained that several farmers present with elevated creatinine—the telltale sign of kidney stress—alongside liver inflammation, malaria, and typhoid. “You can’t say all organ failures are from agrochemicals, but high exposure definitely plays a role,” she pointed out.

Beyond human health, environmental costs are mounting. According to Joyce Brown, director at HOMEF (Health of Mother Earth Foundation), “Routine use of pesticides doesn’t just kill off target pests; it devastates the microorganisms that keep soil fertile. Once destroyed, productivity eventually suffers.”

There are also risks beyond the farm. Yakubu Uwaidem, a crop protection specialist, highlighted that plants absorb chemical residues, which then pass into food for human consumption. A 2021 academic study from Osun State confirmed that many common crops readily retain harmful traces, underscoring the need for better farmer education on pesticide types, doses, and appropriate application methods.

Some farmers are bucking the trend. Damian Edeh, an engineer and traditional ruler in Amankpaka Nike, Enugu East, uses only animal manure to fertilize his modest plot. “Yields are actually better than what chemical users get,” he asserted, citing research and advice from doctors on the dangers of agrochemicals. Edeh collects all his family’s food from his farm and even exports produce to his children abroad. For his neighbor Jude Eze, agrochemicals reduce hard labour—but he admits, “Cassava from non-chemical farms always yields more after processing.”

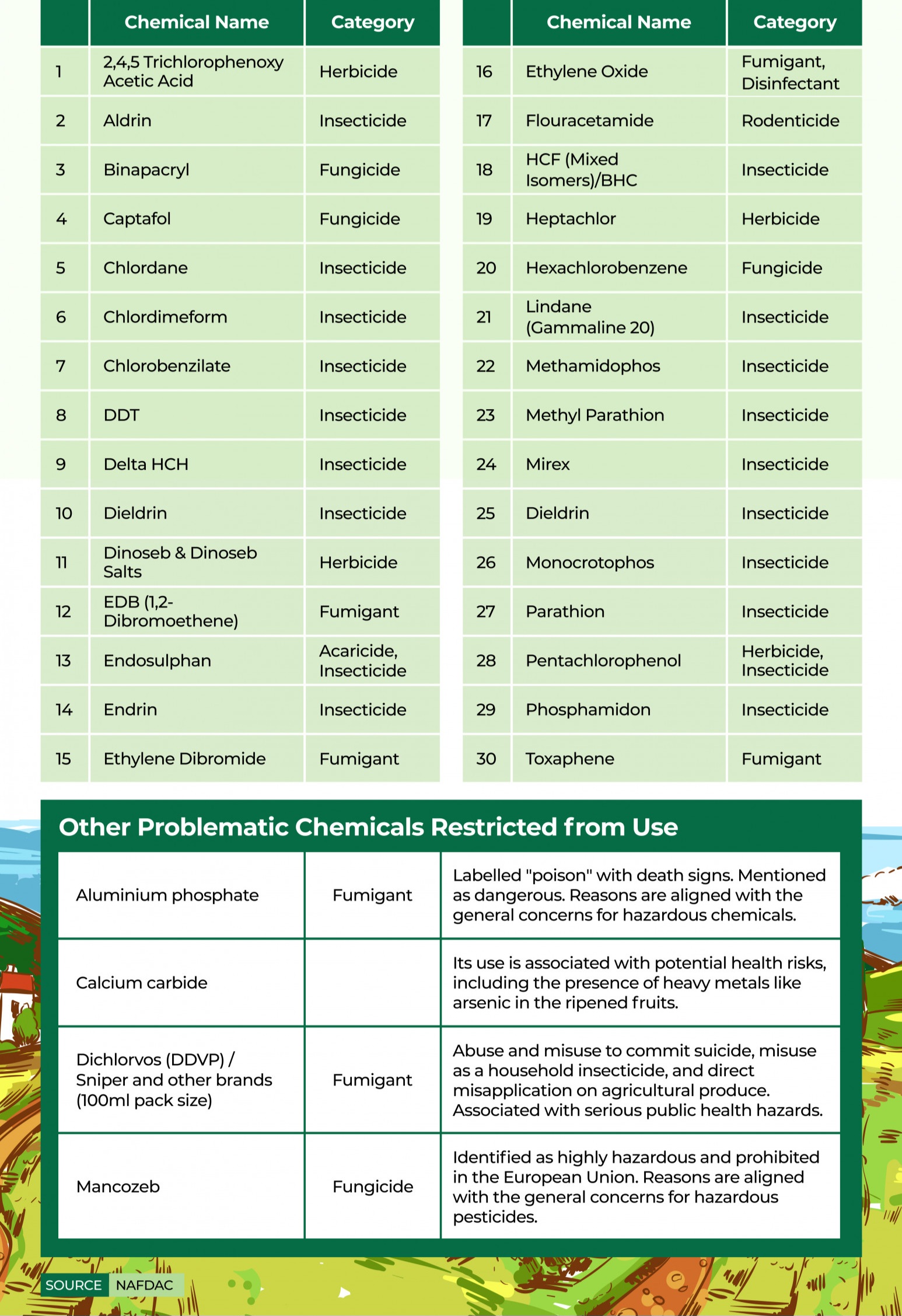

Outside Nigeria, regulation tells a different story. The European Union (EU) has banned dozens of hazardous pesticides after finding evidence of severe harm to human health and the environment. Still, according to multiple reports, some EU countries reportedly export banned chemicals to less-regulated markets, including Nigeria. In 2018, more than 81,000 tonnes of these hazardous products found their way into low-income countries across Africa, with Nigeria importing over 147,000 tonnes in 2020 alone—exceeding all other regions in Africa.

A 2022 German-led study found that EU-banned pesticides remain in active use on Nigerian farms. According to a separate local investigation, almost 40% of all pesticides in use have already been outlawed in the EU due to their high toxicity. Worryingly, most of these hazardous chemicals are marketed to women in some parts of Nigeria, raising additional health concerns for future generations.

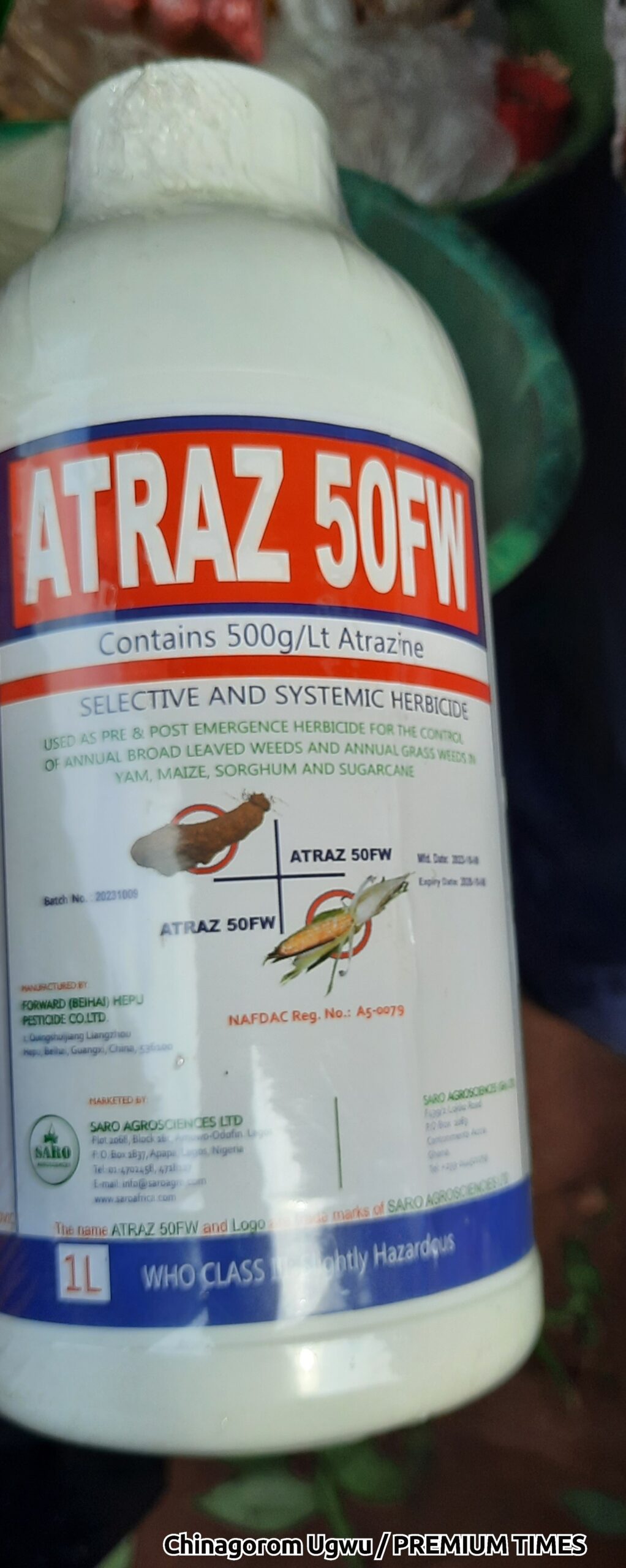

Despite regulations by the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), banned chemicals, such as herbicides with atrazine (linked to cancer and reproductive harm), were still found for open sale in markets across Enugu and Ebonyi as recently as July. Journalists attempting to reach NAFDAC on the issue reportedly received no response.

To mitigate agrochemical poisoning, experts urge Nigeria’s authorities to enforce stricter regulatory oversight at all levels—import, sale, and on-farm use. “Regulations exist only on paper; we need real implementation and accountability,” Prof. Akande emphasized. Joyce Brown (HOMEF) called for an immediate ban on the most hazardous products, the HHPs category, and for empowering farmers to make their own organic pesticides using available products like ginger and garlic, which nurture rather than destroy soil health.

How should Nigeria and West African countries balance the demands of food security with the urgent need for safer, more sustainable farming? What strategies would help farmers reduce reliance on harmful agrochemicals without compromising productivity? Share your thoughts below and join the movement for a healthier future!

Get your story featured or discuss story sales: story@nowahalazone.com

For general support, contact us at support@nowahalazone.com.

Keep the conversation going—drop a comment below, and follow us for reliable news and updates on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram!