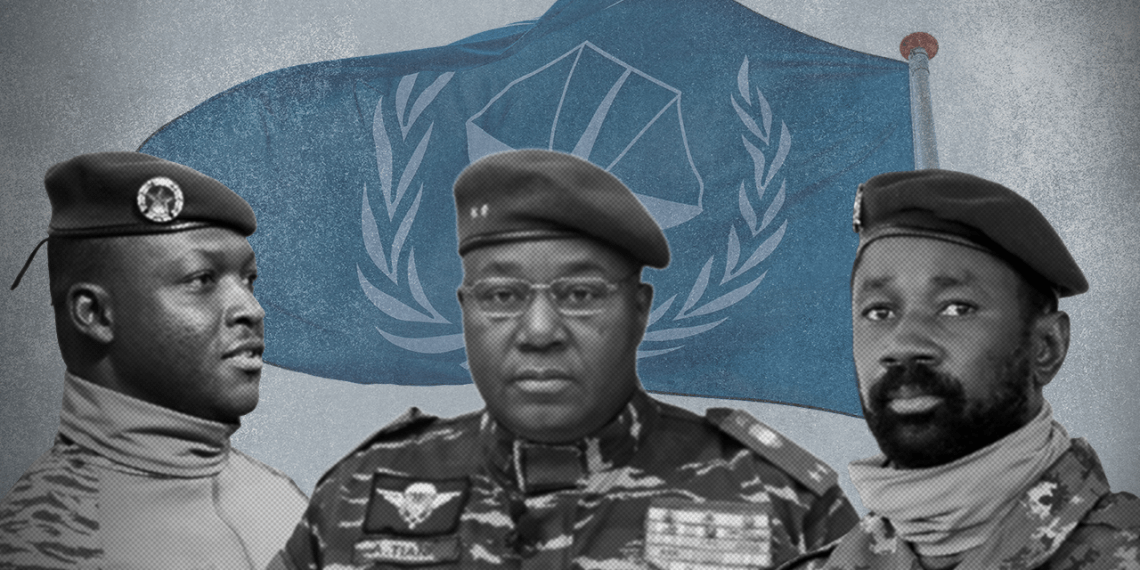

On September 22nd, a significant move unfolded on the international legal stage: the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—comprising Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger—formally announced their departure from the International Criminal Court (ICC). This exit comes on the heels of their earlier withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and its Court of Justice, signaling a broader intent to redefine their engagement with global institutions.

During the United Nations General Assembly, Mali’s Prime Minister Abdoulaye Maïga reaffirmed, on behalf of the AES, that their commitment to global cooperation remains strong—provided such frameworks are truly inclusive. Echoing this stance, the prime ministers from Burkina Faso and Niger also emphasized sovereignty and fairness in international dealings. Interestingly, their addresses did not make direct reference to the ICC, highlighting a calculated focus on broader principles rather than institutions.

A joint communiqué signed by Malian President Assimi Goïta elaborated on their decision, underscoring a shift from reliance on international justice mechanisms toward developing indigenous, community-rooted systems for peace and justice. The AES governments allege that the ICC exhibits “selective” justice, especially in its dealings with African countries—a sentiment that has reverberated across the continent for years.

Complaints about the ICC’s focus on African matters are not new. Between 2009 and 2015, both the African Union and several member countries criticized the ICC for the overwhelming presence of African cases on its docket. Human rights watchdogs like Amnesty International warned in 2022 that this perception of double standards puts the ICC’s legitimacy at stake—a concern that remains alive, especially with the AES’s latest withdrawal.

At this stage, it remains uncertain whether the AES’s departure will spur other African ICC members to reconsider their membership. With over 30 African states currently part of the ICC, mass withdrawal appears unlikely, given that many have recently condemned attempts by global powers such as the United States to undermine the court’s authority on issues that affect the continent.

Africa has played a pivotal role in the ICC’s formation. The continent’s voice shaped the Rome Statute in 1998, and when the statute was adopted, African nations formed the largest voting bloc, cementing a commitment to international criminal accountability. Of the ICC’s current 125 member countries, 33 are from Africa. Despite some withdrawals—Burundi in 2017 and the Philippines in 2019—the trend has largely been one of engagement, with Kenya, South Africa, and The Gambia backtracking or halting previously announced departures.

The journey toward universal ratification and genuine global justice has never been easy for the ICC. Growing criticism from both inside and outside the continent, amplified by the AES’s exit, undeniably complicates these efforts. Many analysts, such as Abuja-based legal scholar Dr. Yemi Ajayi, argue that these developments could slow progress in building a universally respected system of accountability. “We cannot ignore Africa’s influence,” Dr. Ajayi noted in a recent interview, “but this wave of skepticism should motivate reform, not retreat.”

Importantly, African countries have pushed for reforms at the ICC by advocating for the court to investigate cases outside the region. There has been movement in this direction, with ongoing investigations in places like Palestine, Ukraine, Bangladesh/Myanmar, and elsewhere. Yet, the majority of ICC cases still originate in Africa, often as a result of self-referrals from African governments themselves. Notably, Mali referred its own situation to the ICC in 2012—a historic move supported by other West African nations, especially those in the ECOWAS Contact Group on Mali, including Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Niger, Nigeria, and Togo.

Should the AES states fully withdraw, the ICC may continue with its current cases, but cooperation from national authorities would likely dwindle—complicating investigations and potentially slowing justice for victims.

The current political climate across the three countries is shaped by recent coups that brought military-backed governments to power. In Burkina Faso, for example, leader Ibrahim Traoré has championed a pan-Africanist agenda, openly contesting “Western imperialism” and distancing from global entities like the International Monetary Fund and, notably, the ICC. Reports indicate that this rhetoric resonates with many young people frustrated with historical patterns of international interference.

The joint AES communiqué made clear their shared belief that international institutions often serve as tools of Western dominance, applying rules and standards unevenly. Such criticism is not unique to Africa; the United States, for instance, has long refused to join the ICC, citing fears that the court could be used against its interests and those of its allies, including Israel.

Earlier this year, the AES announced plans to create a Sahelian Criminal and Human Rights Court to address regional crimes and human rights abuses. According to the alliance, this initiative is designed to be free from what they describe as “imperialist interference,” rooted instead in local customs and realities. Some legal experts, like Niger-based analyst Fatimata Dogo, have called this a “bold but risky step,” arguing that without independent international oversight, such mechanisms might lack the impartiality and capacity to deliver justice for serious crimes such as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Human rights advocates across West Africa and beyond have voiced concerns that withdrawing from the ICC could expand the “impunity gap,” leaving survivors of atrocities with fewer avenues for justice. In both Burkina Faso and Mali, for example, rights groups claim that war crimes and crimes against humanity have allegedly been committed over the past decade. According to Lagos-based advocacy group JusticeNOW, “The ICC isn’t perfect, but its presence serves as a critical last resort for victims whose voices are otherwise silenced.”

The stance adopted by the AES contrasts sharply with their leadership role during the Rome Statute negotiations in 1998, when all three countries were among the first to ratify the court’s founding document. Their earlier enthusiasm for a multilateral accountability mechanism stemmed from aspirations for fair, impartial, and global standards—a vision many Nigerian observers say still resonates in a region grappling with insecurity and injustice.

While the AES announced an “immediate” exit from the ICC, the Rome Statute stipulates a mandatory 12-month period before the withdrawal becomes effective. This transitional period has, in the past, given countries such as South Africa time to reconsider and ultimately reverse their decisions. Given the AES’s previous follow-through on leaving ECOWAS, however, few local watchers expect a change of heart.

Many legal experts in West Africa see this move as both a blow to international justice and a test of the balance between state sovereignty and accountability. The decision raises essential questions: can regional or local mechanisms credibly replace the checks and balances provided by the ICC? What message does this send to other nations contending with impunity and abuse?

Despite its challenges, the ICC was never intended to completely supplant national or regional justice systems. Instead, it operates on the principle of complementarity—acting primarily when domestic structures are unwilling or unable to provide justice. As Benin-based human rights lawyer Chike Uwagbo noted, “Multiple forums for accountability—from criminal courts to truth commissions—give victims choices and strengthen the fight against impunity.”

Ultimately, the credibility of any justice system—whether local, national, or international—rests on a few foundational principles: no one, regardless of status, should be above the law; legal processes must offer genuine options for victims; and those harmed must retain the right to full participation and redress.

If the new mechanisms proposed by the AES fall short of these standards, critics argue that the move could represent more than a shift in strategy—it could signal a deeper erosion of hard-won norms around accountability and human rights on the continent.

What do you think—can local justice systems in West Africa fill the gap left by withdrawing from the ICC? How should Nigeria and neighboring countries respond to the changing international landscape? Drop your thoughts in the comments and follow us for the latest updates.

For general support, reach out at support@nowahalazone.com.

Join our community for more news and analysis—follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram!