Kyuntu John, a mother of three living on the edge of Abuja, is facing an all-too-common struggle: her ration of antiretroviral medication for HIV/AIDS is about to run out, and the next resupply is uncertain. Her situation echoes a growing crisis faced by countless families in Nigeria and across Africa as access to life-saving drugs becomes an uphill battle.

This crisis has deepened following significant reductions in United States funding for healthcare in Africa under the administration of former President Donald Trump. Billions of dollars once allocated towards international medical assistance, including HIV/AIDS treatment, malaria, and tuberculosis programmes, were drastically slashed, leaving vulnerable populations to grapple with shrinking resources and broken supply chains.

Reportedly, nearly all US foreign aid was frozen shortly after President Trump took office. Despite various legal wranglings and vague promises to restart “humanitarian” programmes, disruptions continue to plague Nigeria’s healthcare sector, and the effects are being felt at the grassroots level more than ever. For Mrs. John, this means not only a dwindling supply of essential medicine, but also the loss of transport stipends that helped her reach the only hospital dispensing the drugs, located four miles from her home in Karonmajigi, a modest neighbourhood on the outskirts of Abuja.

During her last clinic visit, she expressed apprehension to her doctors about the foreign aid cuts and pleaded for an extended supply of medication.

Mrs. John is one of thousands of Nigerians—especially pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers—scrambling to secure vital HIV medication before their supplies run out. Shortages now risk not only the health of individuals, but the broader fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the continent.

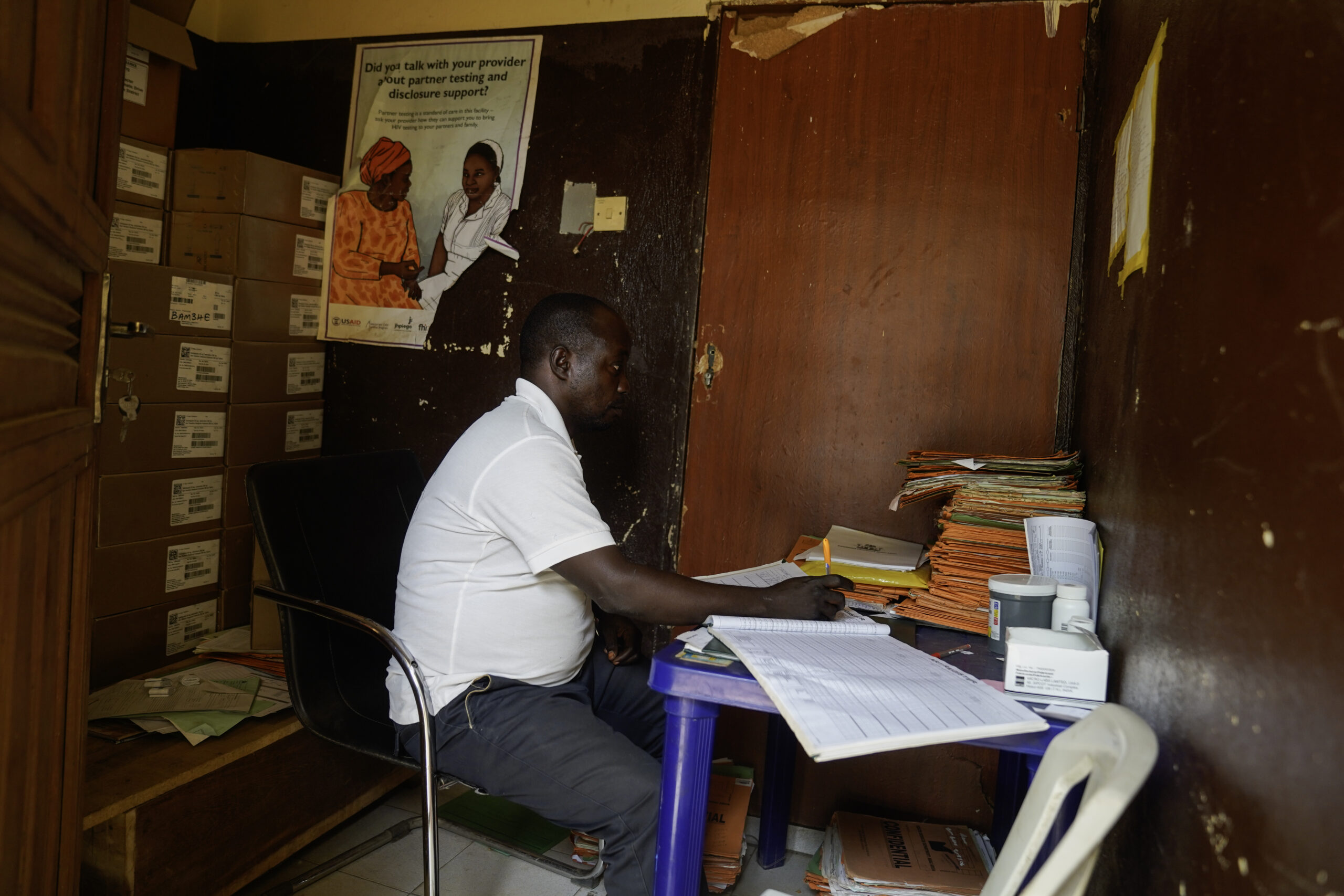

The withdrawal of funding has also hit other crucial US-backed health projects. According to the Nigerian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, staffing shortages have been exacerbated as many health workers were temporarily laid off due to funding gaps.

Researchers at Boston University have estimated that the fallout from US funding cuts could result in thousands of preventable deaths among women and children globally as resources dry up.

“And I don’t have transport fare to the clinic.” she added. A return trip now costs about N2,500 (around $1.60), a sum she finds difficult to afford with no steady income and three children to support.

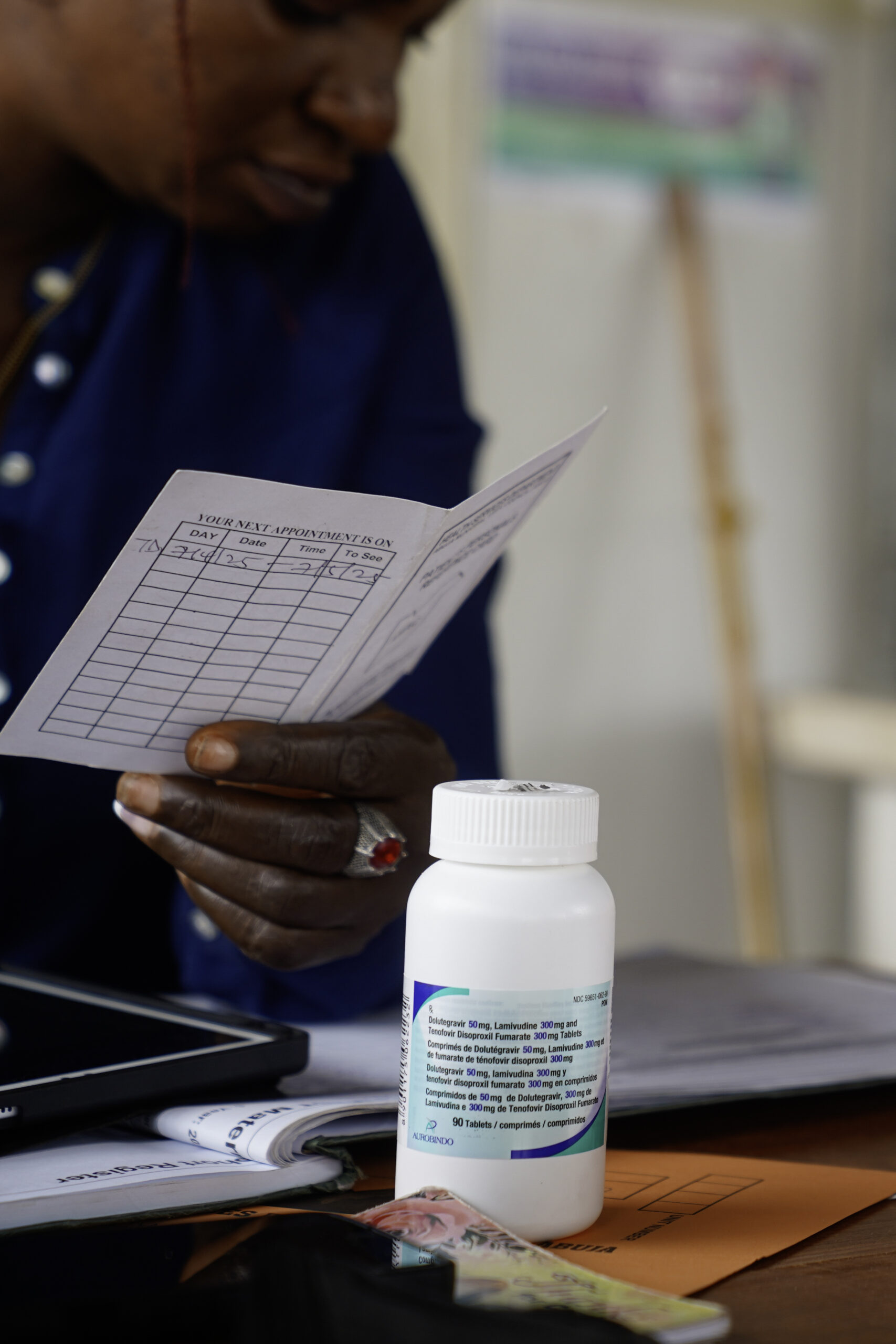

Since the US aid cuts, Nigerian patients who formerly received a half-year supply of antiretrovirals are now sometimes left with only a three-month allowance or less—meaning more frequent, costlier visits and increased risk of treatment lapses.

As a result, vulnerable populations across Nigeria, especially expecting and nursing mothers, are reportedly struggling more than ever to access reliable, ongoing care.

Patients Going the Extra Mile for Life-Saving Treatment

Esther Ina, a 25-year-old mother, recently trekked for 40 minutes to collect her antiretroviral medication at the Lugbe clinic—with her infant tied to her back. She explained that she’d made this exhausting journey twice in the last half-year, compared to just a handful of trips two years ago when refills lasted longer.

“There are many women in situations like this—some even under my supervision,” said Tina Amos, a counselor at the same clinic.

Health professionals interviewed by the Centre for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ), speaking anonymously due to workplace restrictions, reported that patients go without drugs, while medical workers are overburdened. More frequent visits for refills take up valuable appointment slots, reducing the ability to see urgent cases. Ongoing layoffs, they noted, have only increased pressure on those who remain.

When Drug Shortages Force Hard Choices

Previously, HIV patients in Nigeria had to travel every month for their medication. Advocacy by health professionals led to a positive shift: from 2020, three-month dispenses became common, later extending to six months by 2022. Civil Society Networks on HIV and AIDS in Nigeria highlighted that these changes drastically improved access and reduced strain on frontline workers.

However, deteriorating economic conditions—including skyrocketing transport costs caused by subsidy removal, currency devaluation, and inflation as outlined by government and economists—have compounded access issues. Many women, seeking anonymity and protection from stigma, travel far from their communities to collect medications, thus incurring higher costs in both time and money.

Risky Compromises: Skipping Dosages to Make Supplies Last

The current scarcity means that some pregnant women interviewed by CCIJ now skip doses to make their medicine go further. “I skipped my doses in February, after I went to the health centre in Gwagwalada and couldn’t get drugs,” revealed Blessing Christopher, who was pregnant at the time.

Medical experts, such as Dr. Deborah Ubieko of the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, warn that this practice significantly endangers both mothers’ and babies’ health. According to national HIV statistics, more than two million Nigerians live with HIV, and the country’s health ministry records over 9,000 new pediatric HIV cases annually. Reports from UNICEF in 2022 indicate that progress in HIV care for children has stalled, with many babies remaining undiagnosed or untreated.

A Decades-Long Global Partnership in Jeopardy

Nigeria’s HIV response has long depended on foreign support. Launched in 2003 under President George W. Bush, the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has been the backbone of this fight. According to the US Embassy in Nigeria, PEPFAR has accounted for up to 90% of HIV programme funding in the country.

Data compiled by CCIJ points out that from 2015 to 2024, the US contributed an average of $270 million per year for Nigerian HIV programmes, and between 2003 and 2024, over $6 billion was invested, largely through PEPFAR. Most of this money was channeled via international NGOs and Nigeria’s National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA).

However, recent US cuts have led to a sharp decline in available medicines and a noticeable drop in the quality of services. Hospitals in high-burden states such as Akwa Ibom, Benue, and the FCT, Abuja, are reportedly struggling to meet the demand for care. Some clinics in states like Akwa Ibom, Sokoto, and Plateau were temporarily closed earlier in the year and later reopened at reduced capacities, according to local health officials and community organisations.

In Kebbi State, the withdrawal of US funds caused a drastic reduction in services, with healthcare spokespersons stressing the urgent need for local government intervention to avert worsening health outcomes.

Everyday Struggles: The Human Toll of Medicine Shortages

Benue State, where HIV prevalence is among the highest in Nigeria according to NACA, illustrates the real-world impact. Happiness James, aged 32, learned that drugs at her local clinic in Gboko had stopped being distributed for free. “If they start selling, I cannot afford it. It felt like my life was over, and all I could do was cry,” she lamented.

James further explained how shortages of Septrin—an antibiotic vital for protecting her infant from pneumonia, malaria, and other infections—forced nurses to direct her to local pharmacies, where the drug costs about N2,500 monthly. Even though Septrin is cheaper than antiretrovirals, many mothers like James and Deborah Nongom (a breastfeeding resident of Rice Mill, Benue), struggle to balance these costs with feeding their families.

“I just want things to go back to how they were before,” Nongom said, hoping for improved drug supply to keep herself and her baby safe. Healthcare worker Esther Alkali confirmed that her facility has not received Septrin resupplies in months, forcing parents to seek alternatives at increased personal expense.

Beyond Antiretrovirals: A Widening Gap in Basic Healthcare

It’s not just medications that are in short supply. According to Joseph Grace, a health professional in Makurdi, the volume of medical supplies arriving at his clinic has been steadily declining. Routine items, including HIV test kits, are now hard to find.

The Gboko clinic is frequently unable to test pregnant women for HIV as part of their initial check-up—a critical step in preventing mother-to-child transmission. Only women able to purchase kits from private pharmacies can be tested, but this is out of reach for many, especially those traveling long distances from rural areas. Alkali estimates that her facility sees 170 pregnant women a month, making the test kit shortage a major public health risk.

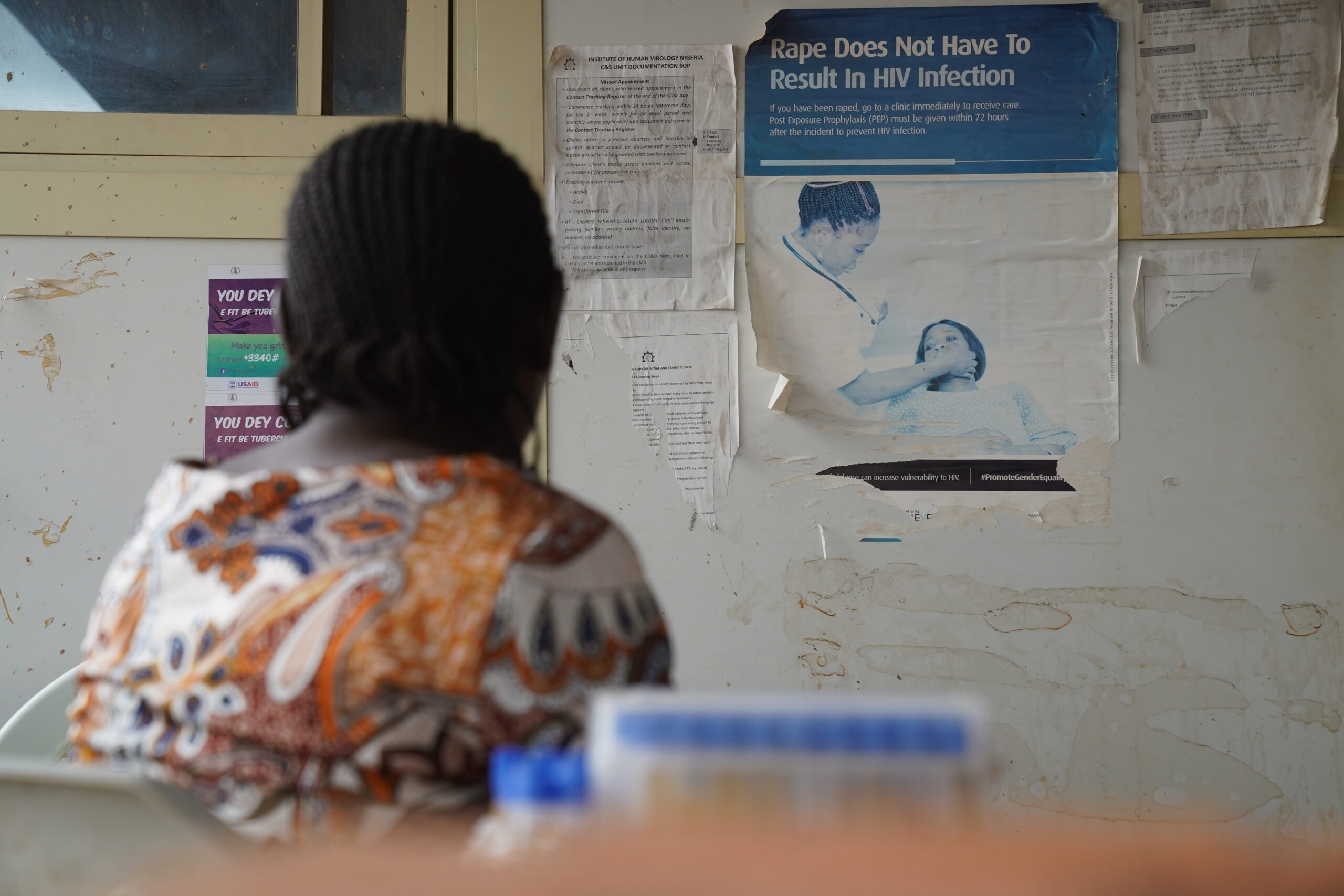

Frontline workers state they have been “overwhelmed” since the discontinuation of once-routine government programmes, including the provision of preventive antiretroviral medicines to individuals at high risk. The end of critical prevention initiatives reportedly impacts sex workers, sexual assault survivors, and partners of people living with HIV as well as mothers and infants.

“Everything changed after the Trump administration’s policies,” said Kate Korave, director of the HIV Testing Service in Gboko. “And the changes were drastic.”

New Efforts and the Road Ahead: Local Solutions Needed

To mitigate this crisis, the Nigerian government has begun to backstop some of the lost funding. In February, the Federal Executive Council approved a N4.8 billion ($3.1 million) injection into HIV programmes, with support from the World Bank and other global partners. The Senate has budgeted an additional N300 billion for health sector funding in 2025. Plans are also underway for the National Agency for the Control of AIDS to begin producing HIV-related supplies domestically, such as test kits and drugs.

However, these efforts reportedly fall short of the financial needs—a CCIJ review claims Nigeria previously received an average of $270 million annually from the US alone to fight HIV.

Health workers and nonprofit groups who once depended on USAID warn that Nigeria’s progress against HIV/AIDS could stall or reverse if local funding doesn’t ramp up. “Nigeria has to scale back its dependence on foreign assistance,” said Aaron Sunday of the Association of Positive Youths with HIV in Nigeria.

Rimamnunra Grace, who leads the Aids Prevention Initiative in Nigeria (APIN) in Benue, summed up the challenge: “The most important thing is that we pick up on the procurement of the drugs. That’s where the work is. If that is not in place, then there is nothing we are doing.”

As Nigeria and other West African nations seek to strengthen homegrown healthcare responses, the fate of people like Mrs. John, Ms. James, and thousands of others depends on whether domestic solutions can fill funding and supply gaps left by international partners.

How do you think Nigeria and other African nations can best secure sustainable healthcare funding, especially with global support becoming less reliable? What steps should communities, governments, and international partners be taking to protect the most vulnerable? Share your perspectives and join the conversation below.

Got a story on healthcare, community challenges, or inspiring local solutions you’d like to share or sell? We want to hear from you! Email us at story@nowahalazone.com to get featured or discuss story sales.

For news tips, support, or to share your opinion on this topic, contact us at support@nowahalazone.com.

Join the discussion and get the latest updates by following us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

Your voice matters. Let’s work together for a healthier Nigeria and Africa!