A closer look at Africa’s debt landscape exposes a deeply rooted contradiction: nations rich with untapped natural resources are also among the most debt-burdened, struggling with poverty, infrastructure shortfalls, and governance challenges. Nigeria and Ghana, two West African powerhouses, are emblematic. According to Reuters, Ghana remains hindered by a protracted debt crisis, while Nigeria contends with liabilities reportedly devouring around 75% of its revenues and an external debt bill exceeding $24 billion. Across both nations, borrowing has not always equated to meaningful change—an issue mirrored throughout much of Africa.

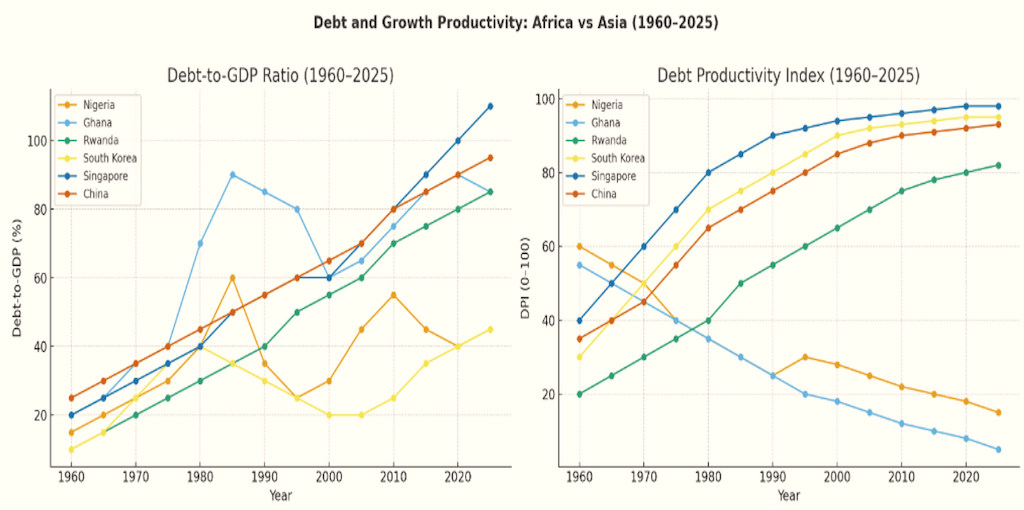

On the other hand, a handful of countries have demonstrated that disciplined, strategic borrowing can ignite growth rather than deepen financial distress. Rwanda, though facing its own surge in debt-to-GDP from about 20% in 2010 to a projected 80% in 2025 (a jump which led Fitch to downgrade its ratings), has invested its borrowings in core sectors like transport, healthcare, and digital infrastructure. This mirrors the experiences of Asian economies such as South Korea, Singapore, and China—nations that turned extensive borrowing, coupled with robust governance and long-term planning, into a springboard for rapid development. Their examples show that the key question for African policymakers is not whether to borrow, but how to channel debt towards lasting, productivity-driven prosperity.

The concept of the Debt Productivity Index (DPI) has emerged as a useful tool for evaluating whether borrowed funds are truly catalyzing growth. By tracking the relationship between debt-to-GDP and per capita GDP growth, this metric brings critical insight: is the continent’s debt creating real economic value, or simply fueling a costly cycle?

Take Nigeria as a case in point. After reaching a debt-to-GDP ratio of 56.6% in 1990, Nigeria’s ratio dropped to under 40% following the GDP rebasing. Despite this, Nigeria’s DPI has consistently deteriorated—a pattern also seen in Ghana, where debt-to-GDP ratios spiked above 80% twice in recent years. Rwanda presents a sharp contrast: even as its debt-to-GDP soared past 80%, its DPI improved, reflecting investments that translated into measurable productivity gains.

Lessons from Asia reinforce this message. South Korea’s government debt is expected to cross 53% of GDP by 2028, China’s could exceed 110% by 2029, and Singapore’s is forecast to hit 175% by 2025, according to the Financial Times and other credible sources. Crucially, these rising debt loads have powered transformative growth, due largely to their productive deployment.

Africa’s Debt: More Borrowing, Fewer Gains

Over the last decade and a half, countries across Africa have seen their borrowing soar—often with little to show in terms of sustainable development or inclusive growth. According to the latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) data, the median debt-to-GDP ratio in Sub-Saharan Africa will reach 60% in 2025, twice the level recorded in 2010. Nigeria’s 45% ratio is below the regional average, yet its fiscal pressures remain daunting. Ghana’s ratio, by contrast, far surpasses 80%. Sudan, meanwhile, is still trapped in a cycle of chronic debt distress, according to the World Bank.

A closer examination of Africa’s debt structure reveals heavy dependency on external sources—Eurobonds and bilateral lending (most notably from China). Homegrown debt markets remain underdeveloped, largely due to limited savings and fragile financial systems. Further complicating matters, global economic shocks, commodity price fluctuations, and rising international interest rates have made the cost of servicing this debt unsustainable for many African governments, leaving public coffers stretched and priorities unfunded.

Africa’s paradox extends even further. Despite substantial natural and human capital, the continent faces persistent power shortages, food insecurity, and capital flight—illicit outflows that, according to UNCTAD, reportedly top $89 billion annually. For nations like Nigeria, high debt servicing means less money for critical sectors like health, education, and infrastructure, undermining long-term development prospects and discouraging badly needed investment.

Rwanda’s Approach: Borrowing as a Tool, Not a Trap

Rwanda provides a notable counterpoint within Africa. Underpinned by forward-looking strategies such as its Vision 2050, the country has consistently prioritized investments in productivity drivers—transport, ICT, and healthcare. Robust governance structures, coupled with close cooperation with donor agencies and multilateral banks, have supported Rwanda’s ambition despite a steep rise in debt-to-GDP. Importantly, these borrowings are aimed at areas with a strong potential for economic transformation—a sharp departure from the patterns seen in some larger neighbours.

Asian Lessons: From Heavy Borrowing to Economic Take-off

Nigeria and other African countries can draw valuable lessons from Asia’s rise. In South Korea, the “Miracle on the Han River” was built on government-led borrowing, invested in industrialisation, compulsory education, and export-focused manufacturing. Singapore similarly used debt in the 1970s and 1980s to fund top-notch infrastructure and develop its workforce. From the late 1970s onwards, China made strategic use of debt to propel infrastructure and technological advancements, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty.

What these success stories have in common, experts argue, is unwavering commitment to long-term plans, sturdy institutions, and channeling debt into projects that tangibly boost productivity. Conversely, in much of Africa, borrowing has too often been a response to immediate revenue gaps, political pressures, or short-term consumption needs. Often, funds are absorbed by wasteful or politically driven projects, while weak institutions and corruption limit the impact of available resources—a point made by many analysts, including those in Lagos and Accra.

Reinventing Debt: Recommendations for Productivity and Growth

Financial experts and civil society advocates across Nigeria and Ghana have called for a new direction. The path to lasting prosperity will not be found in endless debt restructurings alone but through bold, systemic reforms. Among the most pressing recommendations:

- Ensure that borrowing is integrated with concrete development plans and credible, measurable goals.

- Broaden the domestic tax base and improve tax compliance, reducing overreliance on both oil earnings and loans. Analysts caution that the lack of public trust in Nigeria’s 2025 tax initiatives, as outlined in studies by PwC Nigeria, has hampered progress and highlights the need for transparency to foster compliance.

- Deploy debt to fund projects that create actual, measurable growth rather than finance recurring deficits or politically motivated spending.

- Strengthen democratic and institutional oversight to curb inefficiencies and enforce accountability in fiscal decisions.

- Guard against misappropriation of borrowed funds and rigorously assess public investments for clear, long-term returns.

- Treat debt as a catalyst for national transformation, not a quick fix for short-term budget needs.

The window for action is narrowing. As debt service costs rise and new borrowing opportunities dwindle, the risks for future generations grow ever more serious.

A Future Beyond Perpetual Debt

The Nigerian and Ghanaian experience underscores a crucial reality: the continent’s debt burden is not merely a fiscal challenge, but a systemic one—rooted in the structures of governance, accountability, and long-term vision. Rwanda, South Korea, Singapore, and China have proven that, with the right policies, even sizable debt can be an engine for prosperity. Nigeria and its West African peers must now close the gap between liabilities and productivity, focusing not just on managing debt, but on leveraging it to drive inclusive, sustainable growth for all.

What practical reforms do you believe could help Nigeria and other African countries turn debt challenges into engines of growth? Share your thoughts in the comments and follow us for more in-depth analysis on Africa’s economic future.

Do you have a tip, opinion, or story about Africa’s economy, debt, or governance that you want to share or see featured? We’d love to hear from you! Email us at story@nowahalazone.com to send us your story, offer insights, or discuss story sales. For general support, contact us via support@nowahalazone.com.

Connect with the NowaHalazone community for the latest business news, analysis, and updates! Follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

What’s your perspective on Africa’s debt paradox? Drop your comment below and let your voice be heard!