Across Nigeria, dairy farmers are finding it increasingly difficult to keep their businesses afloat as the market floods with cheaper, imported European fat-filled milk powder (FFMP). Several local dairy farms have shut down, and some operators have decided to leave the industry entirely, opting for ventures they see as more financially secure.

During a recent investigation, multiple Nigerian dairy farmers voiced their belief that the country could produce enough milk to meet local demand if the sector received the necessary development and investment. For now, however, the lack of support and unfavorable market conditions make it nearly impossible for them to compete with low-cost imports.

As it stands, Nigeria imports at least 60% of its total dairy consumption, with the majority coming from Europe. According to national statistics, Nigeria spends about $1.3 billion annually on imported dairy products, while local production stands at only around 600,000 tonnes of milk each year.

A major factor behind insufficient local production is that many indigenous cattle breeds deliver low milk yields—often just 1 to 2 litres per day, compared to over 30 litres from specialized foreign breeds. While authorities highlight this as a leading cause, dairy producers point to chronic underinvestment and lack of government support as equally important contributors to the sector’s stagnation.

In a joint investigation with a UK media partner, PREMIUM TIMES uncovered a mix of domestic challenges stifling local dairy growth. Meanwhile, multinational companies from Ireland and other European nations have recognized a market gap in Nigeria and are targeting consumers with affordable milk substitutes.

These imports mainly arrive as fat-filled milk powder, a blend produced by mixing skimmed milk with vegetable oil after milk fat extraction. The product is cheaper to manufacture and transport, and has a longer shelf life than fresh milk.

Investigations in 2023 revealed that fat-filled milk powder is routinely marketed to Nigerians as real milk, although it falls short of international purity standards stipulated by the EU Common Market Organisation (CMO) regulation, which requires milk to remain unaltered.

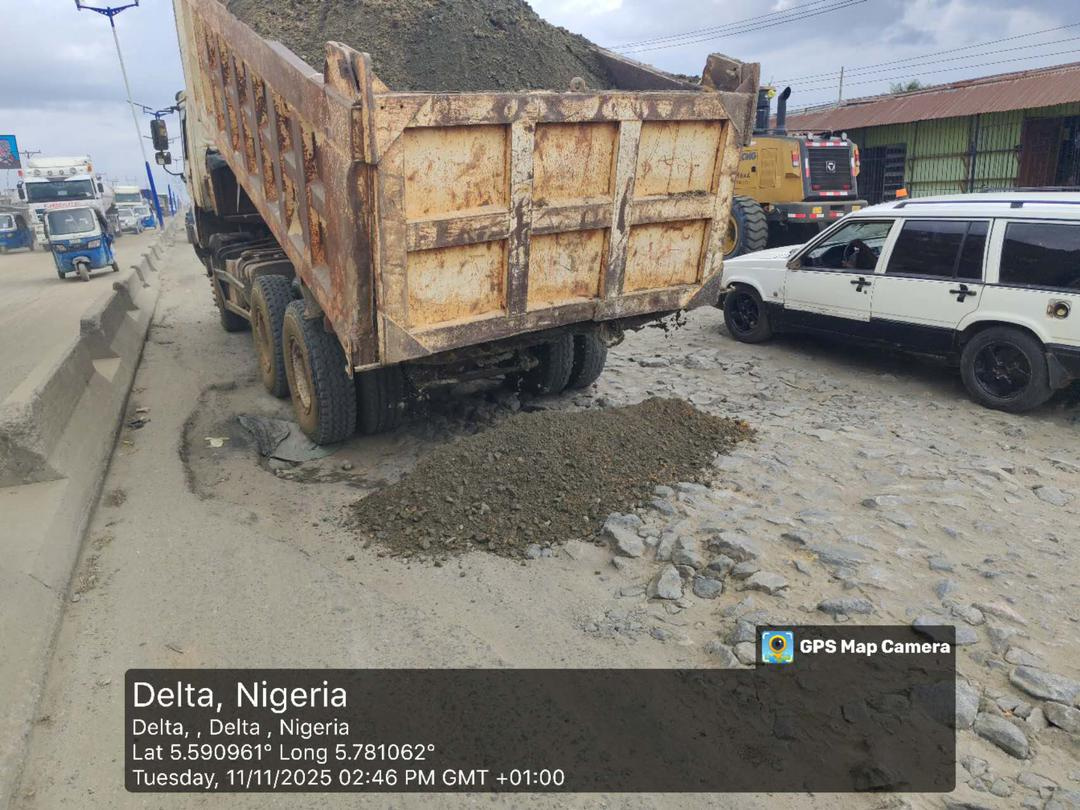

As these lower-cost alternatives dominate the market, local dairy operators continue to grapple with threats ranging from insecurity and inflation to insufficient infrastructure and support from authorities. Farmers say the result is chronically high operating costs and shrinking profit margins.

“Because of these challenges, many dairy farms shut down within five years,” noted Daniyan Abimbola, a commercial dairy farmer based in Osun State.

Surviving Harsh Realities: A Farmer’s Perspective

Mr. Abimbola shared that he is now considering selling both his farm and milk collection centre in Ishiro, a community in Osun, which he opened in 2019. Rising costs have made it nearly impossible to keep operating.

With unreliable electricity and poor road access, Abimbola spends more on fuel for generators, transportation, and cooling equipment needed to preserve milk quality. Add costs of hiring trained staff, veterinary care, and purchasing high-quality cattle feed, and the business becomes difficult to sustain.

Other farmers echoed his frustrations, lamenting that overhead costs eat up most of their earnings. “I want to step back,” confided Mr. Abimbola. “If the situation doesn’t improve, maybe I’ll sell the land, move to the city, and seek a fresh start. I feel like I’m just watching my dream fade away.”

Hamisu Buratai, CEO of Arwaski Farms in Nasarawa, explained that the sector’s slow development means products made from fresh local milk are much more expensive than those made from reconstituted powder, which appeals to price-conscious consumers.

Supply chain weaknesses also plague the industry. Poor infrastructure and significant distances between pastoral communities and milk collection points make aggregation and transportation difficult, leading to frequent spoilage and losses.

These logistical challenges are particularly damaging given that smallholder and pastoralist producers are responsible for about 95% of Nigeria’s milk output.

Security concerns further compound the problems. In northern regions, where much of Nigeria’s raw milk originates, attacks by armed groups have disrupted agribusiness and displaced entire pastoral communities. For instance, a 2022 attack on the Bobi Grazing Reserve in Niger State halted major dairy operations just as large-scale production was set to begin. Kenneth Ahaneku, Director of Neon Dairies Plc, claimed that the incident resulted in losses of up to N20 billion, leaving the company in limbo since.

Despite the quality of their milk and dairy products, many farmers remain discouraged and unable to scale up, according to Dianabasi Akpainyang, Executive Director of the Commercial Dairy Ranchers Association of Nigeria (CODARAN).

European Subsidies and the Global Milk Powder Trade

European dairy companies enjoy significant advantages on the world stage, largely due to generous subsidy programs. One such initiative, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), provides direct payments and extensive market supports to EU farmers, helping keep their costs low and allowing them to export competitively priced reconstituted milk products around the globe.

The CAP, launched in 1962 in Brussels, initially focused on food security and market stability but gradually evolved into an engine for global competitiveness. Subsidies under CAP allow dairy companies to buy surplus milk at reduced prices, process it into powder or FFMP, and easily export it.

According to reports, Irish farmers have received roughly €50 billion in CAP support since 1973. Output surged further after the ending of milk production quotas in 2015. As reported by the Irish Farmers Journal, Irish milk output jumped 50%, reaching 8.4 million litres in 2024, up from 5.6 million litres in 2014.

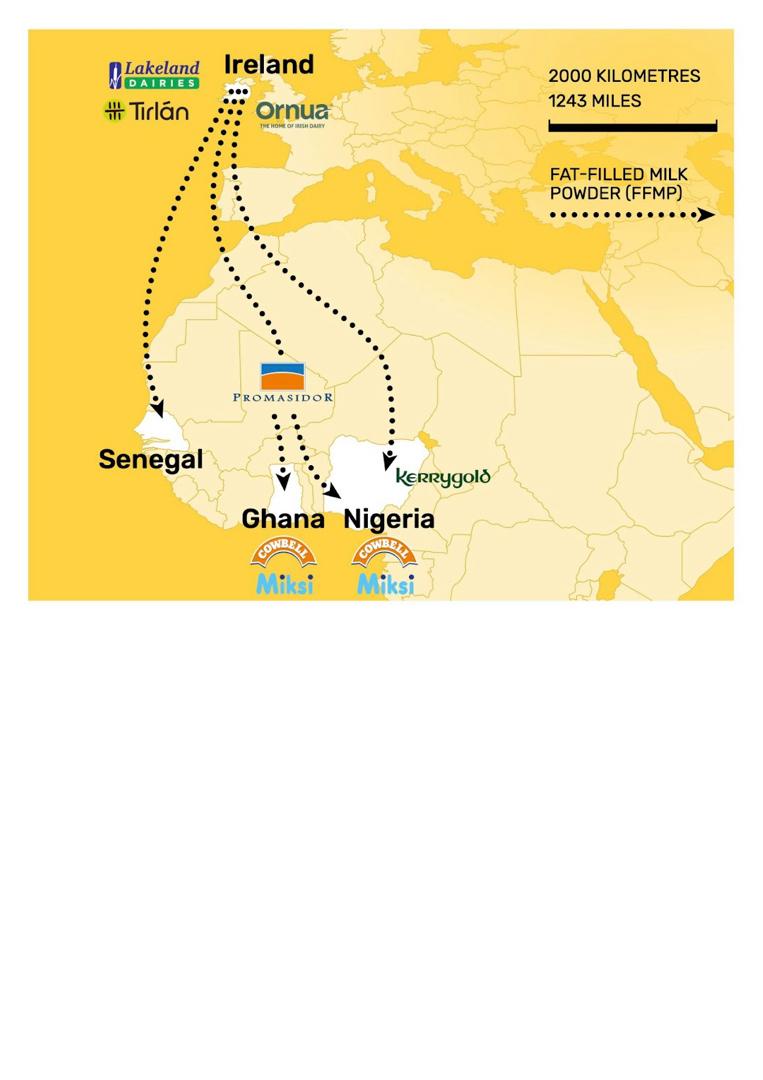

Trade data shows major Irish suppliers to the Nigerian market include Lakeland Dairies, Ornua, The Milk Company, and Tirlán. Ornua, for example, delivers the popular Kerrygold Avantage fat-filled powder, while Lakeland Dairies markets through Promasidor, makers of Cowbell and Milksi brands.

Analysts like Adrien Trouvadis of the West African NGO GRET argue that such subsidies distort international prices, artificially lowering the cost of European dairy products. “This is how European dairy can arrive in Africa so cheaply,” he said, labeling it an “unequal system” that unfairly undercuts African farmers.

On the other hand, Eoin Murphy, Research Officer at Ireland’s Agriculture and Food Development Authority (Teagasc), noted that Ireland simply produces far more dairy than it can consume domestically and thus must export most of its production. He emphasized the role of FFMP in the country’s export model.

By contrast, Nigerian dairy farmers receive little to no subsidies or structured state support, putting them at a severe disadvantage on the world market.

Unlocking Local Potential: Missed Opportunities

Local nutrition experts like Abiola Olaniran of Landmark University, Kwara State, contend that Nigerian dairy farmers are being overwhelmed not by lack of potential, but by multinational companies exploiting the country’s inability to meet growing domestic demand. Cheap European imports continue to appeal to price-sensitive Nigerian shoppers.

Dianabasi Akpainyang from CODARAN also attributed Nigeria’s growing import dependency to policy neglect and underutilized resources. Despite having some 20.6 million cattle—the highest on the continent—Nigeria lags behind countries like South Africa, Morocco, and Tunisia in milk production. These countries have much smaller cattle populations but have achieved double Nigeria’s milk output, primarily by introducing high-yield foreign breeds such as Friesian, Jersey, and Ayrshire cows, or through crossbreeding strategies.

While Nigeria’s cattle are well adapted to local conditions, their limited milk productivity remains a challenge. Other African countries have tackled this through targeted investments and crossbreeding, but Nigerian commercial farmers claim they lack access to funds required for such capital-intensive improvements.

Another hurdle is access to finance. According to officials from the Ministries of Agriculture and Livestock Development, there are currently no government-backed loan or grant schemes tailored specifically to the dairy industry. This, coupled with difficulties in meeting bank criteria for collateral and record-keeping, means most dairy farmers struggle to raise the capital needed to modernize their operations.

Policy Reforms and Market Dynamics

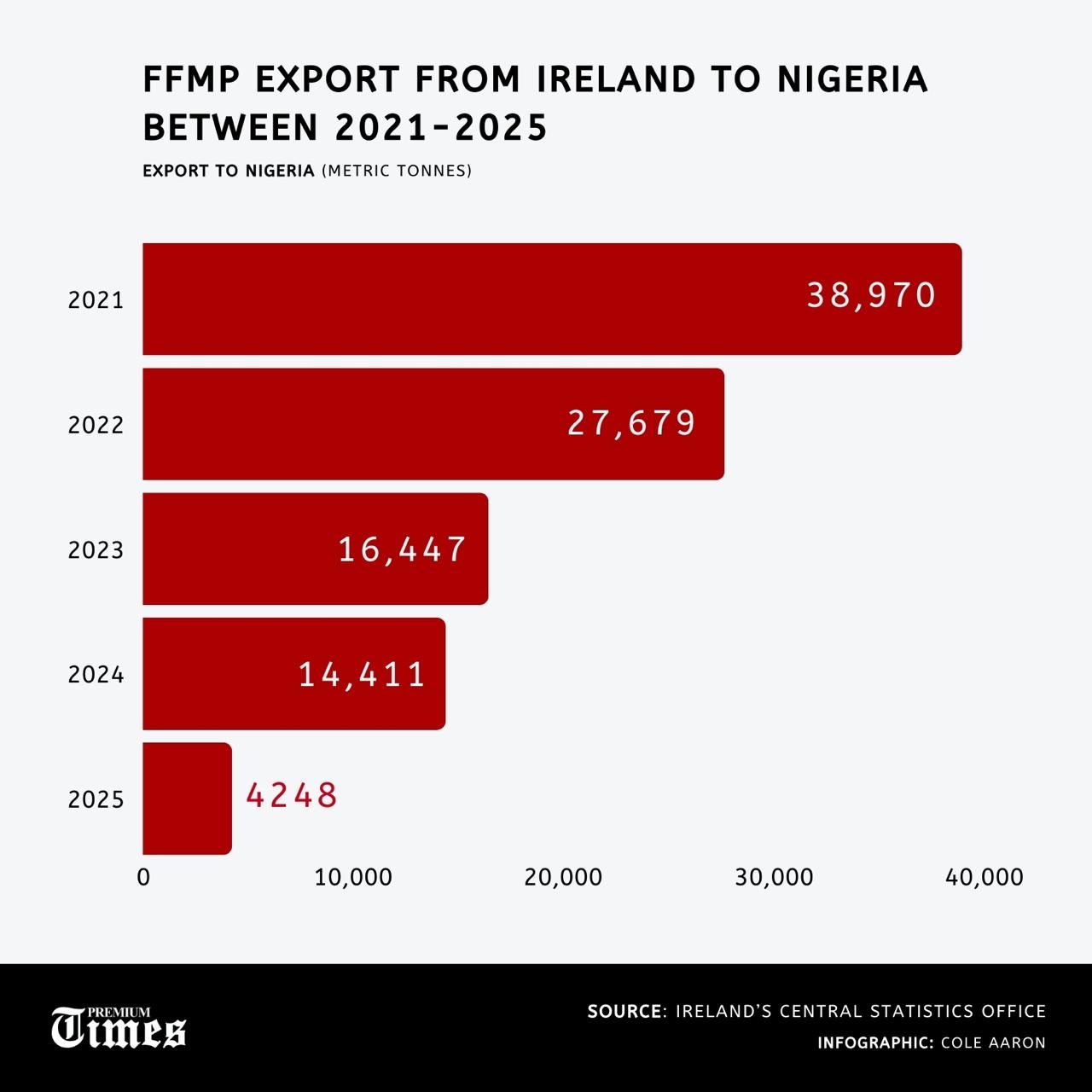

Recent trade data shows a modest decline in Irish dairy exports to West Africa, attributed by the Irish food board Bord Bia to evolving government policies and changing attitudes toward dairy imports. Exports to the region dropped from over 100,000 metric tonnes in 2021 to about 62,000 metric tonnes in 2023, according to DeSmog. In Nigeria specifically, imports fell from 38,000 metric tonnes in 2021 to just 14,000 in 2024, following currency exchange restrictions imposed by Nigeria’s Central Bank in 2020, limiting access to foreign exchange for dairy imports.

This restriction was part of Nigeria’s “Backwards Integration” policy, aimed at reducing reliance on imports by compelling companies to invest in local production. The forex limitation was reportedly reversed in 2024, yet imported FFMP still dominates shelves.

Nigeria remains the top destination for Irish FFMP in West Africa, accounting for nearly 30% of regional exports. Over the past five years, more than 100,000 tonnes of milk products flowed into Nigeria, while Irish companies exported over 400,000 tonnes to West Africa overall between 2020 and 2024.

According to DeSmog, Lakeland Dairies, Tirlán, and Ornua, collectively earning €7.8 billion in 2024, were the top FFMP exporters to Nigeria and Ghana in recent years.

Yet, the outcomes of backward integration policies have been underwhelming. Attempts by multinational dairy companies to build local production capacity have stumbled due to insufficient government support, funding gaps, and, in some cases, alleged labor abuses or insecurity. For example, a major milk farm project in Kaduna with Danish company Arla stalled when state funding was not provided, while child labor allegations surfaced at FrieslandCampina WAMCO’s Oyo State operations. Furthermore, the Bobi Grazing Reserve project, a collaboration with multiple dairies, was derailed by security incidents.

Neon Dairies’ Kenneth Ahaneku expressed disappointment: “We moved to Bobi at the directive of the Central Bank, invested millions, and then lost everything in violent attacks. No government compensation or promised loans. It felt like a Ponzi scheme.”

Funding Gaps and the Struggle for Reform

The newly formed Ministry of Livestock Development has also had a challenging start, with an initial budget of only ₦11.8 billion for 2025—an amount lawmakers criticise as insufficient for a new agency. According to Maidugu Shuaibu, senior officer at the ministry, this allocation barely covers administrative costs, stalling meaningful sector investment.

Until last year, livestock—including dairy—was subsumed under the broader Ministry of Agriculture, where crop-focused plans took precedence, leaving the dairy industry with scant resources. The 2024 launch of the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock was designed to bridge this gap, but effective sector revitalization will require more robust funding and long-term policy commitment.

“The ministry is just a year old, but without further investment we can’t progress,” Shuaibu observed. “We’re encouraging international companies to undertake backward integration, but these projects will take years to bear fruit.”

Marketing Trends and Local Consumer Response

Ireland’s state food promotion agency, Bord Bia, has actively promoted Irish dairy in Nigeria. Between 2021 and 2024, collaboratives with Ornua invested more than €80,000 in consumer campaigns timed around World Milk Day and other trade missions. One 2023 trade presentation highlighted the “aspirational” nature of Nigerian consumers and stressed the importance of brand-building, even among lower-income citizens.

Despite the slick marketing, internal documents reportedly revealed little engagement with the challenges facing local farmers or support for Nigerian dairy industry growth. Ultimately, Bord Bia hailed the trade mission as a success, with Irish clients meeting over 300 potential partners and identifying “significant potential” for future agri-food sales in West Africa.

Advertising and Regulation Issues

Dairy brands like Ornua and Lakeland Dairies have used celebrities and social influencers to popularize fat-filled milk powders, blurring the line between alternative products and real milk. Nigeria’s food regulatory body, NAFDAC, confirmed in 2023 that FFMP can only be marketed as a milk alternative—not as milk itself. However, research by DeSmog and PREMIUM TIMES found that many online adverts failed to make this clear and even overstated the products’ nutritional value.

Promotional material on social platforms frequently referred to Kerrygold Avantage as “milk,” with influencers touting it as a “protein source.” Similar claims were made for Milksi, which was advertised as containing “all the calcium, proteins and vitamins essential for children’s growth.” Food experts warn that such endorsements can mislead consumers, especially when the celebrities involved might not actually use the products themselves.

While Nigeria has clear nutritional and economic incentives to boost local dairy output, transforming the industry will require consistent funding, better infrastructure, tighter regulation, and stronger support for smallholder producers. The conversation around dairy in Nigeria is not just about the product on the shelf—it’s about livelihoods, food security, and the future of rural communities.

What do you think needs to happen for Nigeria’s dairy industry to compete globally and meet local demand? Share your thoughts and experiences below, and don’t forget to follow us for more updates on this evolving issue.

For general support or tips, contact support@nowahalazone.com.

Connect with us for the latest updates—follow us on Facebook, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

Your story can make a difference—let’s amplify Nigerian voices together!